By Guy J. Sagi

Full metal jacket bullets have an outer shell made from one metal, with a softer interior core manufactured from another—the latter typically being lead. FMJ is the firearm industry’s shorthand for the design, although some militaries and enthusiasts refer to it as “ball.”

FMJ loads are full metal jacket ammo and are most commonly used by shooters for range training or during competitions that require high-volume shooting. These rounds are not designed to expand on impact with a soft target, making them a poor choice for self-defense or hunting in most scenarios.

FMJ Bullet Design

The copper-coated FMJ bullet reduces barrel fouling and is cleaner to shoot than other non-coated ammo options.

Lead was ideal for the spherical projectiles in early firearms, thanks to its relatively low melting point, abundance and energy-carrying mass. As gun designs improved—bringing with them higher muzzle velocities, increased chamber pressures and a departure from single shots. The malleable metal’s drawbacks in bullets also became obvious. It fouled barrels, deformed with eerie regularity on exit and even made chambering a second round from newfangled magazines a hit-and-miss affair.

Swiss Col. Eduard Rubin discovered a solution in 1882 when the mechanical engineer tested a bullet with its lead core enveloped in copper—the first FMJ. His experiments determined the tougher and higher-in-melting-point exterior minimized fouling and, thanks to copper’s reduced willingness to bend unpredictably, improved cycling of fresh rounds into a firearm. In addition, the layer of slightly lighter material had little impact on the bullet’s ability to retain energy downrange and the projectiles were not deforming.

Modern FMJ Manufacturing

An expanded view of FMJ pistol (top) and rifle (bottom) ammo, note the lead core visible on the 9mm bullet.

It caught on fast and the design is probably the most common encountered at the range today. There’s good reason, too. Advances in technology have made FMJ bullets more uniform and accurate than ever before.

Modern manufacturing of an FMJ begins by shaping the material that will become the jacket into a uniform cup. Companies typically use copper although they continue to discover and harness a variety of advantages offered by other alloys.

Core material—usually swaged lead wire—then goes into the cup and pressure applied to draw the jacket over it. This removes issues like air pockets or other performance-robbing inconsistencies at the same time. Lead lends itself extremely well to the process due to its ductility.

The final steps are shaping, trimming and inspection. The manufacturing process leaves some core material visible at the base of the bullet, even after it’s finished.

FMJ Advantages

FMJ rifle caliber bullets are known for their accuracy and reliability, even in adverse climate conditions.

FMJs are inexpensive, a fact reflected in the price of factory ammo loaded with the bullet design. That makes them ideal for high-volume shooters, competitors and plinkers.

They may be budget-friendly, but don’t underestimate their long-distance performance. Even after you’ve learned to adjust for the wind at 1,000 meters, most FMJs outperform the shooter. When you’re ready to dial things up feel free to invest in loads with fine-tuned projectiles, but it’s surprising how this routine firing line fodder is the preferred choice at major training academies.

Cleanup is a breeze, too. If you’re not fond of scrubbing bits of lead from the hidden recesses of your barrel, you’ll appreciate FMJs. Thousands of gun owners owe thanks to Col. Rubin—few know his name, although most appreciate his ingenuity.

Annoying stovepipes and many other “jams” can disappear, too. With lead’s tendency to bend, dig and otherwise defy the purpose of a magazine’s feed lips blanketed in copper, things get more reliable.

FMJs are also better at containing lead when they hit a target. The metal’s dust/vapor is a major concern at some ranges, particularly indoor facilities. This style bullet is mandatory at some facilities, a rule that supplements the cutting-edge ventilation systems always in use.

FMJ Disadvantages

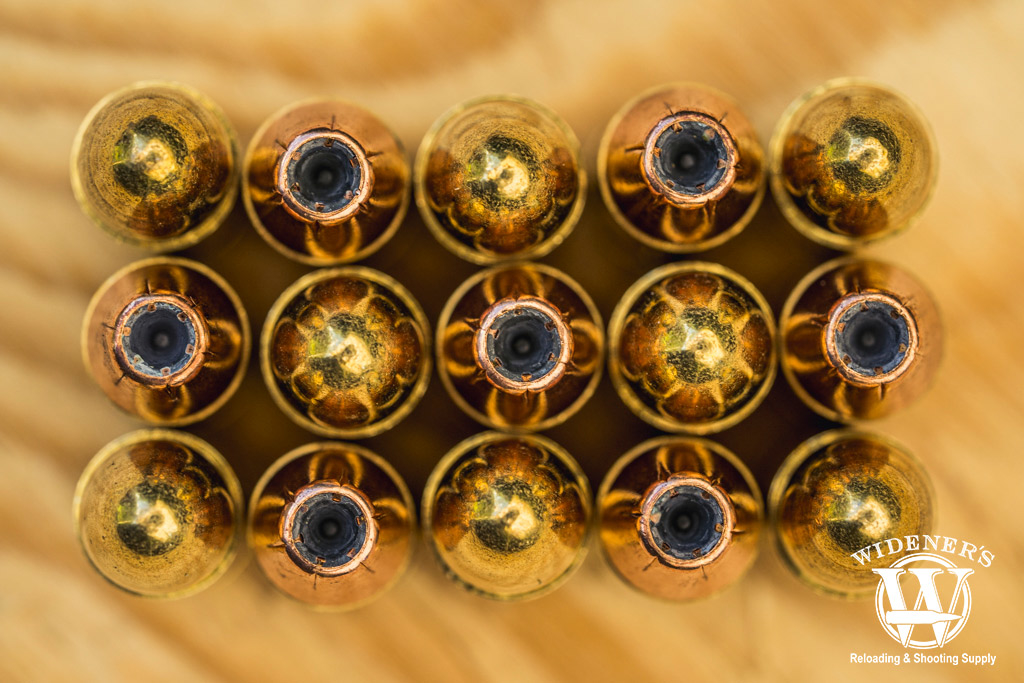

A comparison photo of 115gr FMJ 9mm ammo mixed with 115gr JHP 9mm ammo. Can you spot the differences?

FMJ bullets are notorious for an unwillingness to expand at bullet impact. Terminal ballistics that make this style of bullet style not recommended for self-defense or hunting. They often pass completely through the target, whether it’s a deer or felonious attacker, delivering minimal stopping power. With little loss of kinetic energy, they can keep going through most metal, walls or untargeted animals in the herd until friction and gravity finally grind things to a halt.

There are better bullet designs for those who hunt, carry or are ready to defend their family and home. They’re tailored to maximize energy delivered on the target to ethically take an animal or stop the assault, a task the FMJ doesn’t perform well. The design of the jacketed hollow point or JHP as it is commonly referred to is a much better choice for hunting or self-defense situations.

Plated vs FMJ

A plated bullet is related to the FMJ, visually anyway. The resemblance is there, but the two are not identical. It also has an exterior metal shell, but the manufacturing process explains subtle differences.

To create a plated bullet, manufacturers submerge the core in a solution rich in “jacket” material. The exterior coating collects after the introduction of an electrical charge, an electrochemical technique more often associated with the jewelry industry. The process results in complete coverage, including the base of a plated bullet. Manufacturers stuff the end of the bullet inside a loaded cartridge, so the average shooter who doesn’t reload will never notice.

CMJ vs FMJ

Whether or not these coated metal jackets (CMJs) quite live up to the FMJ family’s fame is a matter of discussion. Those with opinions on the subject often point out some of the finer differences between the two. A plated bullet’s “jacket” material, for example, has not gone through the heavy machining process a pureblooded FMJ undergoes. Without that work-hardening, the former is theoretically more prone to nicks and bends. Those imperfections tend to hang up when traveling from a gun’s magazine into the chamber.

Other often-cited factors include a typically higher price tag, a fact that reflects thicker coatings require a longer stay in the solution. Performance, particularly at long range, can also be a concern. The slightest change in a bullet’s weight distribution—even if it weighs the same—can affect the point of impact. Shooters typically only notice the change when firing at great distances.

FMJ-BT Ammo

The boat-tail bullet design is known for its accuracy and is favored among long-distance shooters.

There are many forces affecting a bullet as it travels downrange. Minimizing their impact increases accuracy, the primary reason long-distance shooters favor boat tail (BT) bullets. Many hunters, competitors, LEO and military marksmen prefer the boat tail bullet design for its precision accuracy.

The design is simple and is visible at a bullet’s base. The sides of boat tail bullet end with a slight taper instead of the more traditional and abrupt 90-degree angle. The best way to visualize the concept is to think of a boat hull from an overhead view. The gentle inward bend at the stern is the BT design, hence the name. It reduces turbulence—even friction—as air passes over and behind a projectile during flight. That makes an FMJ-BT the best choice for anyone shooting at extreme range.

FMJ Ammo Legacy

Although not a great choice for self-defense, the FMJ is a favorite option for those training or plinking at the range.

Although the basic concept of the FMJ remains the same, advances in technology have fine-tuned the design to levels unimaginable by Col. Rubin and his development team at the Swiss Federal Ammunition Factory and Research Center—then considered among the world’s foremost in ballistics research. There’s no doubt they’d marvel at the modern material and manufacturing but appreciate the fact it all remains true to the primary goal, one they accomplished more than 100 years ago.