The Warrior Ethos is part of the Soldier’s Creed and was essential to Roy Benavidez’s life. Though every soldier learns it in basic training, few exemplified it as he did. In the Vietnam War, Sgt. Benavidez distinguished himself with a physical and mental toughness that earned him the Medal of Honor.

I will always place the mission first.

I will never accept defeat.

I will never quit.

I will never leave a fallen comrade.”

– Warrior Ethos (U.S. Army)

Little in Roy’s background points toward the highly-respected hero he would become. Born in Cuero, Texas, on August 5, 1935, Roy Benavidez lost both parents by age seven. After that, his aunt and uncle raised him. While still in school, he shined shoes at a local bus station, worked on farms, and at a tire shop.

Roy dropped out of school at age 15 and began picking sugar beets and cotton to support his family. With few choices for steady employment, he joined the Texas National Guard in 1952 during the Korean War. Three years later, he joined the active-duty infantry and spent time in South Korea and Germany.

Roy Benavidez: One Tough Soldier

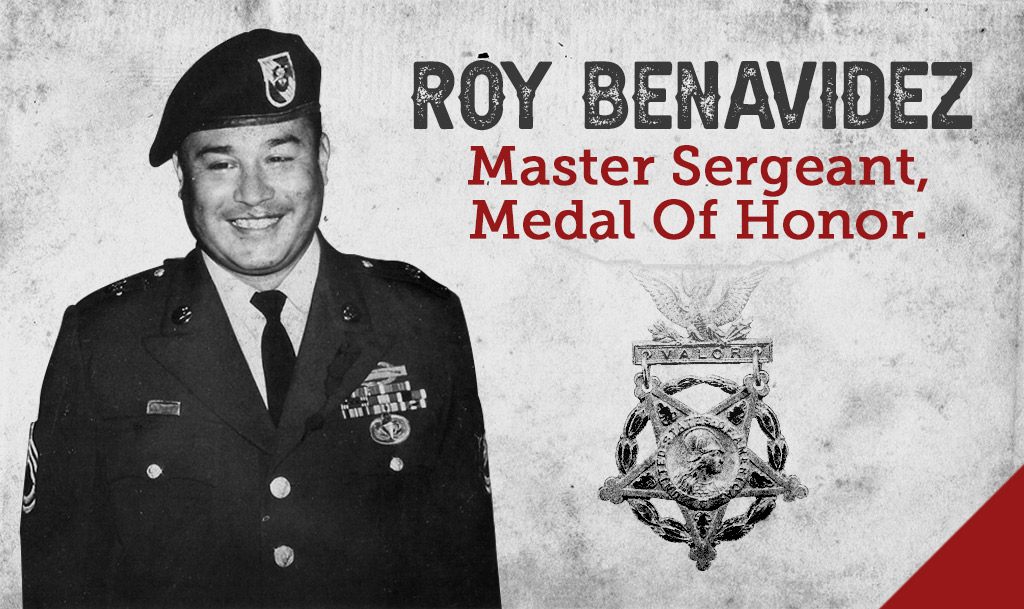

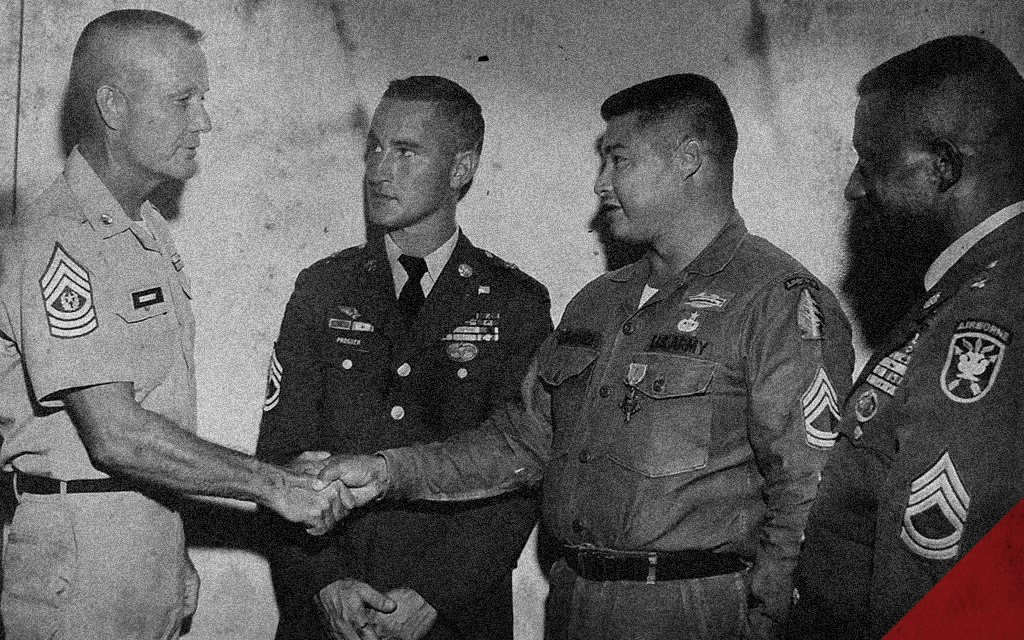

Master Sgt. Roy Benavidez receiving the Distinguished Service Cross at BAMC in 1968. (Image: Benavidez Family)

Roy Benavidez married Hilaria Coy Benavidez and began his Military Police (MP) training in 1959. The same year, he completed airborne training and entered the 82nd Airborne Division. As US involvement in Vietnam ramped up in 1965, Benavidez went there as an advisor to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).

On patrol with an ARVN regiment, Benavidez stepped on a land mine and ended up in the hospital at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines. Then he went to Fort Sam Houston’s Brooke Army Medical Center. Paralyzed from the waist down, with a seriously damaged spine, he faced the possibility of never walking again. He knew he’d likely receive a medical discharge from the service.

But instead of resigning himself to his fate, Roy Benavidez ignored his doctors’ orders and began a tortuous nightly training routine. After crawling over to a wall, he trained until he could pull himself up the wall. Over many months, Royin painstakingly developed the muscles in his legs. After over a year in the hospital, Sgt. Benavidez returned to the Army. There, he received another six months of physical therapy.

Back To ‘Nam

Right after returning to the 82d Airborne, Benavidez could hardly walk. Yet after six months, he was running ten miles in full gear. Training with the elite Studies and Observations Group (SOG), he joined the 5th Special Forces Group and returned to Vietnam. Once back, Benavidez requested an assignment to Detachment B-56 along the Cambodian border.

It was here that Sgt. Benavidez performed several acts of bravery. These later prompted President Ronald Reagan to comment, “If the story of his heroism were a movie script, you would not believe it.”

Six Hours In Hell

Benavidez survived 37 bullet wounds, bayonet, and shrapnel wounds during the six-hour fight with the NVA.

May 2, 1968, started peacefully. Roy Benavidez attended a Catholic prayer service. That ended when a 12-man Special Forces Recon team radioed for an emergency extraction. They’d encountered between 1000 and 1500 North Vietnam Army (NVA) soldiers and needed help.

Carrying only a medical bag and knife, Benavidez jumped on a rescue chopper and took off. When the Huey came within 75 yards of the surrounded men, Roy ran toward them under heavy fire. Though a bullet in the leg knocked him down, and shrapnel from a grenade blast hit him, he continued.

After giving first aid, he repositioned the remaining team members. Benavidez directed their fire to assist the aircraft in landing and loading wounded and dead team members. Benavidez also threw smoke canisters to show the way for the rescue aircraft.

Despite multiple wounds and concentrated enemy fire, he carried or dragged half the wounded team to the aircraft. He then ran alongside them to offer protective fire when it moved to get the remaining members. Under withering enemy fire, Benavidez sprinted to recover the body of their team leader plus classified documents.

After he reached the dead leader, small arms fire wounded him in the abdomen and grenade shrapnel hit him in the back. Then the chopper pilot sustained a fatal injury, causing the ‘copter to crash. Benavidez went to the wreckage, helping the wounded out of the overturned aircraft. He then placed the survivors into a defensive perimeter.

Roy Benavidez: Unrelenting Bravery

Despite enemy fire from automatic weapons and grenades, Benavidez distributed ammo and water to the men. His leadership renewed their will to live and fight back. As the enemy closed in, Sergeant Benavidez called tactical air strikes and directed fire from supporting gunships. His actions held the NVA at bay and made another rescue attempt possible.

When the next helicopter arrived, Benavidez grabbed a seriously wounded team member and headed for the aircraft. As he got there, an NVA soldier that had appeared dead jumped up and bashed him with the butt of his AK-47, breaking his jaw. As the NVA soldier lunged with his bayonet, Roy grabbed it with one hand and used his Bowie knife. The encounter left a slash on his right hand and his left arm injured from the bayonet.

Once again, he attempted to pull his comrade to the helicopter. Then he noticed two more NVA running from the jungle. Benavidez grabbed an AK-47, dropped the two enemy soldiers, and got the severely wounded man into the chopper. Someone finally shoved Benevidez into the helicopter and they took off. As they flew, he grasped his teammate’s hand with one hand and held his guts in with the other.

The Medal Of Honor

President Ronald Reagan awarding Roy Benavidez the Medal of Honor in 1981. (Image: Time.com)

The aftermath of those six hours is almost unimaginable. Sgt. Benavidez received 37 wounds by bullets, shrapnel, a bayonet, and a rifle butt. His actions saved eight men’s lives in Vietnam on May 2, 1968. By the time the details of his heroics came to light, the time limit on the medal had expired. The Army board denied an extension because they required an eyewitness. Benavidez thought there were no living witnesses, but he was wrong.

A radioman named Brian O’Connor had been severely wounded but not killed as Roy had believed. O’Connor saw a newspaper account and immediately contacted Benavidez. He submitted a ten-page report confirming the accounts others provided and serving as the eyewitness.

On February 24, 1981, five years after Benavidez retired, President Ronald Reagan presented him with the Medal of Honor in the Pentagon.

The Death Of A Hero

After he retired, Roy Benavidez spoke to many organizations in several countries and wrote three autobiographical books. He visited American military personnel and sometimes joined them on field exercises. Roy was a favorite of students, service members, and private citizens worldwide.

Master Sergeant Roy Benavidez died on November 29, 1998, at Brooke Army Medical Center. He was 63 when he succumbed to respiratory failure and complications from diabetes. Benavidez went to his rest with full military honors at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery.

One of Roy’s books is titled Medal of Honor: A Vietnam Warrior’s Story. He was a relentless warrior, a family man, and a person of faith. The Medal of Honor belongs to heroes like him. Roy’s story is an example of a well-lived life.