By Guy J. Sagi

A revolver’s method of operation is straightforward, uncluttered, and rugged. It’s arguably the most reliable repeating handgun design ever made, capable of defying conditions that force many semi-automatics to surrender. How revolvers work is so simple and universal that despite many advances in handgun technology, they remain ubiquitous in the firearms world.

Today, the advantages of that simplicity are easy to overlook in an industry awash in headline-grabbing auto-loading pistols with magazines that carry more and more cartridges. Lost in the hype is the fact that revolvers, often affectionately called wheelguns, have proven themselves a lifesaving asset on the western frontier, in combat, and for law enforcement duties. Their performance still shines brightly in self-defense, hunting, and competition.

Their simple principle has remained unchanged for more than 200 years. Modern versions have added safety features, of course, but all remain true to the original approach. A fresh cartridge rotates until it stops at perfect alignment with the single barrel directly in front of the firing pin, ready to deliver the shot.

A quick look at how revolvers evolved illustrates their virtues and why they persist as a popular choice today. Nostalgia isn’t the only reason they deserve consideration. Wyatt Earp, Jesse James, Buffalo Bill Cody, and others helped make them part of American history — but the earliest designs appeared long before they did.

How Revolvers Work: The Mechanics

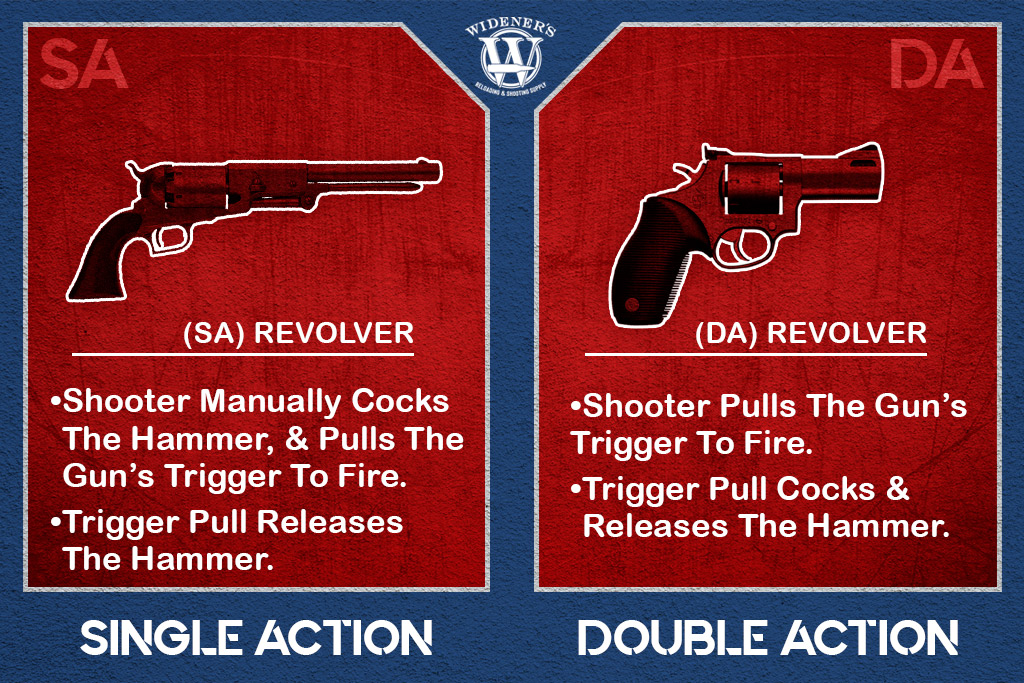

How do revolvers work? The mechanics are simple, a trigger pull releases the hammer, hitting the primer, and firing the gun.

Single- and double-action revolvers share primary mechanical functions. For example, as the hammer moves back on both—manually or during the trigger pull in a double-action—it compresses a hammer spring in the grip and stores the energy required for an effective primer strike.

At the same time, a small pawl pushes a ratchet affixed to the back of the cylinder until the chamber locks in position for the shot. With sufficient trigger travel, the spring releases its energy, pushing the now-released hammer forward, striking the primer.

The bullet then leaves, and you can repeat the process until there are no more fresh cartridges. Even then, you can continue to dry fire.

These designs share another feature—or lack thereof. There are no manual or external safeties on revolvers.

Double-Action VS Single-Action

The trigger of a single-action revolver performs one action, while the trigger of a double-action revolver performs two actions.

Most modern manufacturers have incorporated a transfer bar safety or firing pin block in their single-action revolver designs. These safety devices activate automatically and prevent sufficient force from reaching the firing pin should the hammer bounce or come down without a full trigger pull.

They are highly effective and alleviate safety concerns, but they don’t improve extraction and reloading speed for single-action revolvers. Removing empty brass still requires rotating each chamber to the loading gate and pushing the extractor bar below the barrel.

An advantage to single actions is the elimination of much of the mechanical movement as the cylinder turns and comes to full lock up. It’s done manually beforehand, and that hammer can stay back as long as you want before squeezing the trigger. With less friction between moving parts, trigger let-off weight is often noticeably less than in a double action.

Historical Development

Ninth-century Chinese monks searching for an elixir to prolong life developed gunpowder, and firearms quickly followed. Bamboo formed the earliest barrels, while porcelain balls became the first projectiles. Despite that rudimentary approach, the discovery was groundbreaking.

Dramatic improvements followed, but loading for a second shot remained slow. Adding gunpowder, a patch, and a projectile is a lengthy process when your four-legged quarry is escaping or an enemy is approaching.

Early Innovation: How Revolvers Work

The first solution was multiple barrels, which appeared in a handgun in the late 1400s. The Tower of London is home to one of them, a four-shot matchlock. A three-barreled matchlock made in 1548 (or earlier) is on display today in Venice, Italy.

Those rotating barrel designs—now called pepperboxes—sent more rounds downrange faster than their contemporaries. Their operation, however, was a clunky, two-handed affair. It was rudimentary but another giant leap in firearm effectiveness.

Rotational Beginnings

There were attempts before, most out of Germany, but the first patent for a firearm with a cylinder that rotated a fresh load into firing position came about in 1718. That Puckle gun, a creation of British inventor James Puckle, was a tripod-mounted flintlock with a 3-foot barrel. It wasn’t a handgun, obviously, but it could deliver up to 11 shots without a reload.

One hundred years later, Elisha Collier received a patent for the first true revolver, a flintlock with a single barrel and seven-shot capacity. Its painfully unreliable flint-ignition system doomed it from the beginning.

Samuel Colt Revolutionized How Revolvers Work

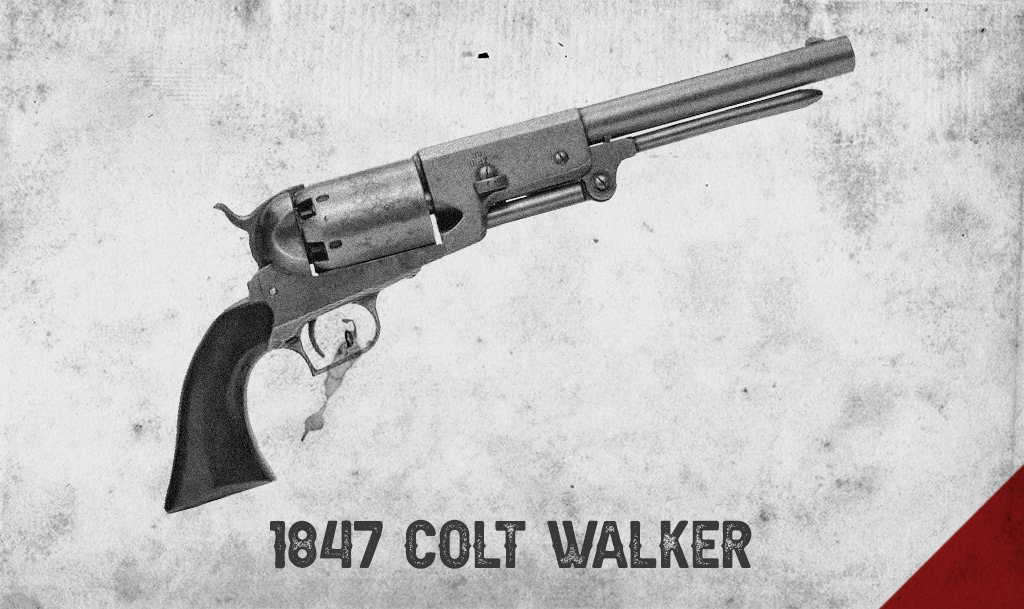

The 1847 Colt Walker, was Samuel Colt’s first successful mass-produced revolver, with 1,100 units produced.

Samuel Colt created the first revolver to withstand the test of time. Colt had an insatiable interest in gunpowder from an early age and used it to put on impressive pyrotechnic displays early in his schooling.

His formal education ended after one of his shows accidentally torched a building. His father sent him off to learn seamanship in 1830, but it did nothing to thwart his firearm enthusiasm. While aboard the ship Corvo, headed to Calcutta, he (as legend has it) studied the capstan’s ratchet and envisioned a similar mechanism in a repeating handgun.

He crafted a wooden version of his first revolver while still at sea. Its chambers were in the cylinder, which rotated and locked in alignment with the single barrel. With practice, one-handed operation was possible, unlike with a pepperbox. It also reduced bulk, which is a big asset for horse-mounted shooters.

Colt returned to the United States in 1832 and applied his talents in other ventures for a time but returned to his passion for firearms. His original design improved after collaboration with gunsmiths in Maryland, and the first prototype received a patent in England in 1835. He followed suit in the United States the next year.

His revolver harnessed the improved ignition of the new percussion cap. That reliability helped make his initial model, the Paterson, a classic. It wouldn’t be until 1847 that the Colt name would gain widespread fame, though. That year, the Texas Rangers ordered 1,000 Colt-made revolvers with features requested by Col. Samuel Walker. The performance of those six-shooting, black powder-burning .44-caliber Colt Walkers launched a legend that now includes the Peacemaker and many others.

Singling Out The Double Action

Each of Colt’s first revolvers was a single-action, which required a shooter to pull the hammer fully back for the cylinder to rotate and align a fresh load. Only then could the shooter successfully pull the trigger and repeat, if necessary.

However, there was a big drawback to this operation. Anyone who left a live load directly in front of the barrel could experience a negligent discharge if that hammer bounced enough to set off the percussion cap—or primer today. Falling off a horse, getting hit by branches, or suffering a drop were common culprits, so many owners keep the top chamber in a single-action empty. Most modern single-action revolvers alleviate this concern by incorporating a hammer block or transfer bar safety.

Double Trouble

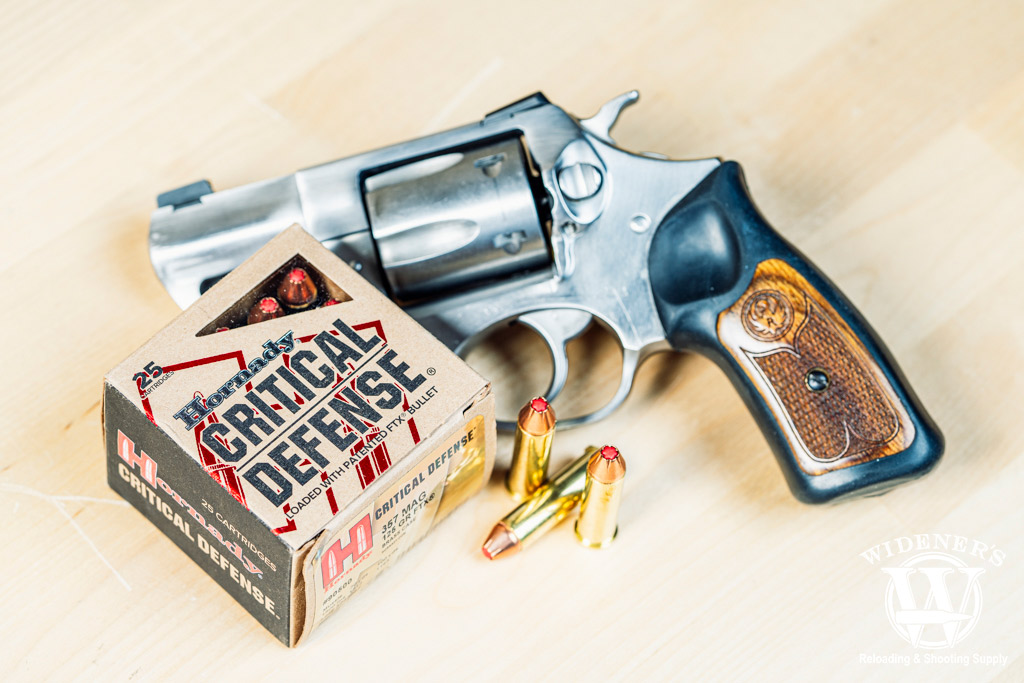

It’s not just the guns that evolved, modern revolver ammo and ballistics have also improved.

Then, in 1851, Englishman Robert Adams received a patent for the double-action revolver. Its headline advantage was a timesaving one. It eliminated the need to manually thumb the hammer back for each shot. Squeezing the trigger rotated a fresh cartridge until it indexed, and continuing that movement fully released the hammer.

The cylinder also swung out to the side of the frame, simultaneously exposing all chambers for reloads. With Adams’ innovation, the entire cylinder rotates out, and with a single press of the ejector rod, all spent brass drops. It’s a huge advantage over a single action, which requires punching brass out one at a time through a loading gate.

Inserting fresh ammunition is also faster, and that pace later improved with the introduction of speedloaders and speed strips. They hold cartridges in pre-shaped forms matching the cylinder, or several rounds staged in a rubberized base that flexes for fast insertion, respectively.

Semi-Auto?

The first semi-automatic revolver patent came in 1839, followed by others in 1841 and 1854. Intellectual rights to a gas-piston-driven version were issued in 1863, but it was not until 1895 that any became commercially available. Even then, only the recoil-operated Webley-Fosbery Automatic Revolver made it to market. It was based on the Colt Single Action Army, with the barrel, cylinder, and hammer sliding back and forth as it fired, rotating to the next chamber and cocking the hammer in the process.

Its last year of production was 1924, largely ending the semi-auto revolver story. There are none made today, but the improvements in modern single- and double-actions are well worth noting.

Modern Doubles

Modern revolvers may be traditional (self-cocking) single or double-action, or (no pre-cocking) double-action only.

Double actions feature the same type of internal safeties, but manufacturers have done amazing things with their handgun designs. Today, there are internal hammers, which reduce snags on clothing during presentation. Trigger let-off weights are better than ever, and something new and innovative is on the market every year.

The advantages of extraction and reloading speed remain, too. With a speed loader (or a couple of speed strips) and some practice, it’s surprising how fast you can get back in the fight.

How do revolvers work? Quite well, and reliably. Regardless of your choice, you can’t go wrong selecting either design. There are good reasons they’ve been around for so long, and they’re not going anywhere soon.