With the politicization of gun rights in the U.S., the AR-15 has become the poster child for both sides. Beloved by gun-rights supporters, the rifle is the ideal representation of the Second Amendment. It’s a non-military-grade tool in the hands of citizens ready to defend hearth and home. Gun control supporters don’t see the patriotic history of the AR 15. They view it as a weapon of mass production, capable of taking countless lives in a whimsical moment of poor impulse control. In reality, less than 1% of deaths in the US involve this rifle. There is no denying that the individual freedom it represents brings the history of the AR 15 into focus for both sides.

The AR-15 had a few false starts in the beginning. Sadly, several bad decisions during its initial deployment cost the lives of an untold number of soldiers. This calamity threatened to relegate the design to the garbage heap of bad ideas, right next to the Chauchat. Yet, over half a century later the design is holding on in active military service. All designs should be so lucky to have such staying power, and to be sure, several features play into this longevity.

What Is The History Of The AR 15?

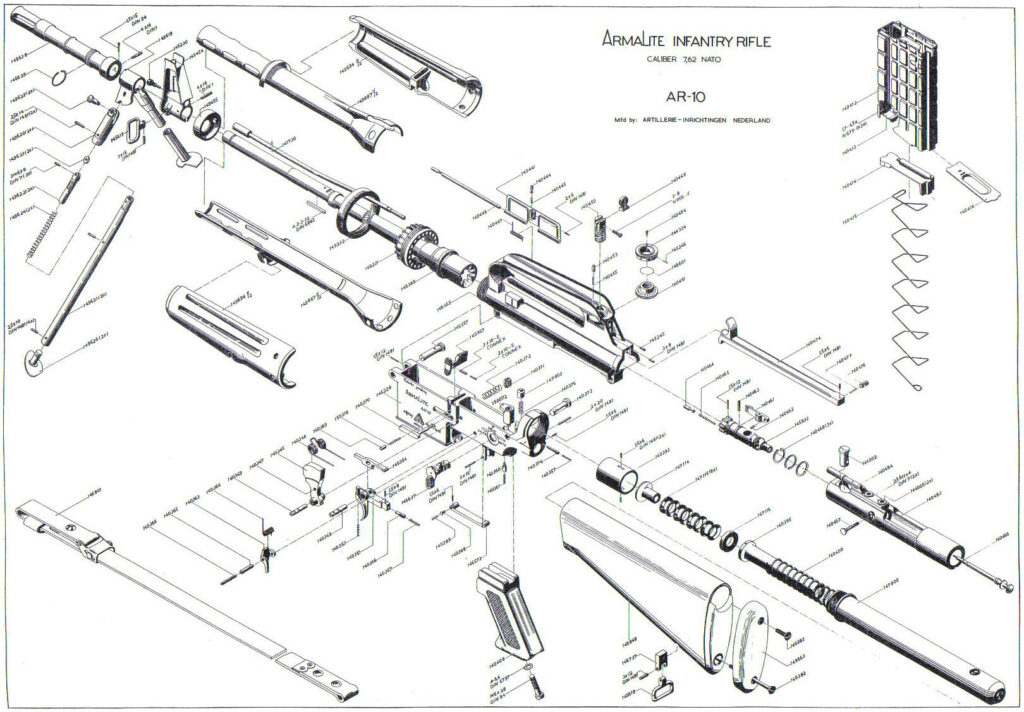

Eugene Stoner presented his Armalite Model 10 design to the U.S. military in 1956. (Source: Armalite)

Introduction Of The Armalite Rifle

The AR-15 gets its designation from the Armalite Rifle Model 15. Eugene Stoner presented his Armalite Model 10 design to the U.S. military in 1956. It was intended to be a replacement for the M1 Garand. The Army needed a new service rifle chambered in 7.62 NATO. Re-chambering the Garand was a short-term solution to getting the U.S. to conform to its new military treaty obligations. This also made for a good opportunity to submit new designs. The military didn’t adopt Stoner’s AR-10 design. Later, other nations, including Spain, considered it and commercial variants made their debut.

The U.S. armed forces decided instead to go with the Springfield M14. Considered by many to be a superior battle rifle for a variety of reasons. It was also heavy, weighing 10.7 lbs with a fully loaded magazine. Many commentators questioned the need for a full-sized rifle given that many engagements of the preceding decades happened much closer than the 600 yards or more performance range of the 7.62 NATO. Other well-informed observers also took note of a new rifle the Soviets had fielded in the 1950s, the AK47.

Remington Arms had been developing a new, small diameter, hypervelocity cartridge for use as a new medium-range rifle caliber. Stoner scaled-down the AR-10 design and presented the 223 in anticipation of the U.S. military demanding a light battle rifle. This became the Armalite Rifle 15.

By 1959, the Armalite company was experiencing financial difficulties and was unable to meet manufacturing requirements to further test and promote the rifle. So, in the history of the AR 15, they sold the design to Colt.

Introduction Of Military Use

The Colt AR-15 uses the direct gas impingement system to cycle the action.

The Colt AR-15

By the early 1960s Colt provided select-fire rifles to the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Special Forces. With U.S. involvement in Vietnam threatening to ramp up in 1963, it became clear that the Springfield Armory was not going to be able to keep up with the production of M14 rifles. The decision to expand production to other companies became proposed, but the cost of M14 manufacturing became an issue to U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

The M14 turned out to be an outstanding rifle, but the costs to manufacture outweighed the pros. Its cartridge required more resources and came to be considered overkill for engagement distances of 300 yards or less. McNamara decreed that the AR-15, be put into full production. Thus, abandoning the M14. These new design functions made it very similar to the M16. It had select-fire capabilities. The new rifle was lighter to carry and cheaper to make. Its ammo was also less expensive and easily controllable on full-automatic fire. It appeared to be a no-brainer.

The 223 Remington Cartridge

The new rifle needed a lot of new ammunition. There were no stockpiles of .223 Remington or 5.56×45 ammunition and the company could not answer the demand of arming all the military branches overnight, especially as U.S. involvement in Vietnam increased. The Olin Corporation, the name behind Winchester, was contracted to make up the shortfall. In the rush to get the ammo, Olin changed cartridge loading from standard Dupont stick powder to ball powder. In turn, muzzle pressure increased, and the rifle’s gas port had to work harder, due to stick powder not burning as quickly as ball powder. This infamously resulted in increased fouling and led to ejection failures on the battlefield.

The AR-15/M16 operates on direct gas impingement, where the expanding gas pushing the bullet out of the barrel is tapped back to cycle the action. This blows gas and carbon directly into the chamber. The burnt gas particles inevitably collect there and build up during firing. This was not all that unusual, it is how self-loading rifles worked since the days of John M. Browning and Hiram Maxim. Stoner’s design does have tighter tolerances than many military weapons to date. The obvious hindsight answer was that the rifle would require cleaning, something soldiers were taught in Basic Training.

Disaster On The Battlefield

1967, Quang Ngai Province, Republic of Vietnam: PFC Michael J. Mendoza (Piedmont, CA.) fires his M-16 rifle into a suspected Viet Cong occupied area. (Source: National Archives and Records Administration)

When the M16 was new and modern when it was issued to combat troops in Vietnam. It fired a new bullet that seemed anemic, but promised to deliver terrible destruction (it did). The rifle misfired during ballistics testing. Military and government leaders knew this. They allowed it still. The M16 was introduced to as a self-cleaning weapon. In theory, sounds helpful to a soldier in the jungle. The combination of damp environment and increased carbon was a recipe for jamming.

The teething problems of using a new weapon design in the middle of a war are almost always tragic. When reports came in of dead GIs being found after combat with their rifles disassembled in a frantic effort to get them working again before being killed, the State Department moved with uncharacteristic vigor.

Ball powder was put back into the ingredients bowl. Training programs taught soldiers how to care for their new wonder weapon. New models were installed with a feature called a forward assist. Initially, many ignored it because there was no other way to manually close the bolt with a non-reciprocating charger. A quick overhaul made the M16 a reliable fighting weapon. Fortunately, its winning characteristics in weight and controllability continued to play out. Especially, on an American soldier who was more often a draftee looking forward to the end of his tour rather than winning a war with no clear set objectives for ultimate victory.

AR Platform Popularity

When the U.S. finally extricated itself from Vietnam, the M16 was the established U.S. military service rifle. Colt had primary control over the weapon design even though it subcontracted components to other companies to meet manufacturing quotas, including apparently Mattel. When the war was over, military contracts dried up. Colt continued making the civilian, non-select-fire, AR-15 for the non-military market.

The AR-15, however, was not a popular civilian rifle. Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, production numbers for the rifle rarely exceeded 3,500 a year. When Colt’s patent on the rifle expired in 1977, there was not a lot of concern.

Sam Colt rarely pursued civilian markets. The company focused on military contracts, which frequently left the company in jeopardy when governments were not buying.

Second, at the time the AR was not a popular rifle anyway. The market was limited pretty much exclusively to Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP) competitions and an occasional veteran or gun enthusiast. The history of the AR 15, from Colt’s perspective, may very well have been a specific purpose tool that the consumer market simply would not support or make worthwhile.

This may be hard for the modern aficionado to grasp. While gun control has always been a political issue, the polarization of recent decades has a lot to do with the popularity of the AR. The media largely directs this narrative. Without prior gun experience, people buy into it. Of course, there is also the issue of gun bans.

The History Of The AR 15 And The Media

The 16″ barrel AR-15 is capable of high accuracy, this target was shot standing at 50 yards.

Criminals have misused the AR rifle in high-profile events. Like the 2002 DC Sniper, 2012 Sandy Hook School Shooting, and 2017 Las Vegas Shooting. This presence makes the rifle the de facto villain to the debunked mainstream media. The media countlessly reports the AR being used when it was not. Like in the 2013 Navy Yard Shooting, when in fact, that attacker used a shotgun and two handguns.

Among the most recent acceptable statistics, the AR-15 is the safest weapon around. In 2011, an estimated 11,000 people were killed with a firearm, 322 were killed with an “assault-style” weapon. This includes AKs and other variants, as well as ARs. While one loss is too many, if saving lives is the goal, if there were a successful AR ban (a big “if”), it would yield comparatively negligible results from a purely objective perspective.

Every year, sales of ARs continue to grow with no increase in shootings.

Once dismissed by Colt, the AR now defines America’s attitudes on gun rights. Two primary factors that make the AR relevant these days. The first is a Federal ban.

Federal Assault Weapons Ban

The Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994 outlawed the AR-15 and other semi-automatic rifles.

The 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban did little to save lives. However, it did do wonders for mobilizing the nation’s gun industry into a political and industrial powerhouse. The ban brought to life the biggest fear that many gun owners have: turning into criminals by legislation rather than their individual actions. With the ban’s sunset in 2004, gun sales enlarged marginally for fear of another ban potentially on the horizon. This fear grew with every tragic event and fed by the words of politicians advocating a ban. It is of small comfort to gun control advocates that former president Barak Obama’s presidency coincided with the greatest sales of AR-15s in all of history. This was not a coincidence.

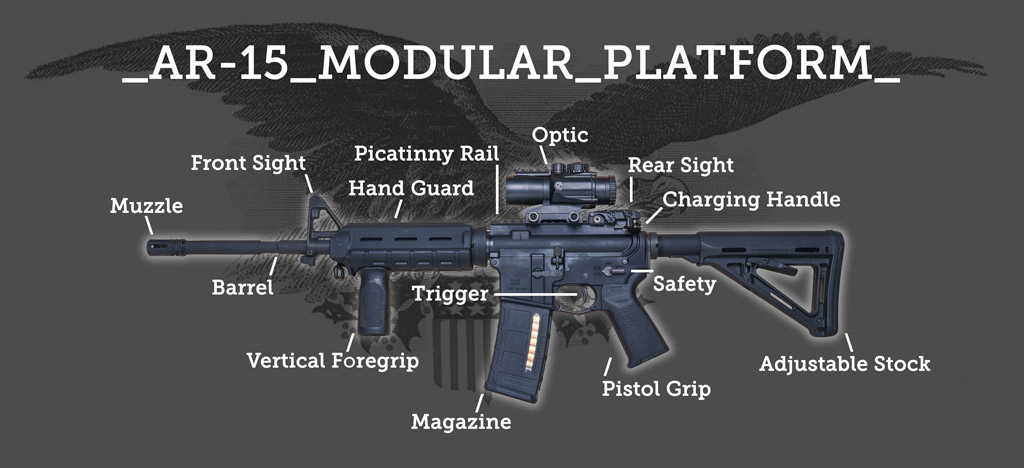

The second primary factor is the gun’s modularity. Virtually every major firearms manufacturer (with the exception of Glock) makes an AR variant rifle. Add to that hundreds of small manufacturers turning out receivers. There are hundreds more making AR-15 accessories. Then there are the 80% receivers that allow a skilled tool user to make their own firearm for personal use (not federally illegal but many states have outlawed it).

Different AR-15 Variations

On the technological end, there have been efforts to upgrade, if not replace the AR-15/M16 platform for military and police purposes. This has led to different calibers such as 6.8mm SPC Remington and .300 Blackout. Just a simple upper receiver swap. The platform can also fire pistol calibers. Again, magazine adapters and upper assembly replacements are necessary, or you can fire .22 LR rimfire with a chamber insert.

The AR-15 is one of the most popular rifles in the U.S. thanks to its availability and versatility.

Further development is to create piston driven system instead of the traditional gas impingement. While technologically interesting, it does not solve the problem that regular cleaning does. For sustained use in situations where cleaning is not possible (e.g. deployment on long assignments in hostile territory) the piston system is of use. However, this makes it a bit excessive for civilian applications.

The Modular Rifle

The AR, despite its technological roots, has become a weapon of the people rivaling the AK47. This would not be possible without the rifle’s modularity: part interchangeability makes the rifle the “Barbie Doll” of gun enthusiasts. Quality and exact fit are always variables among manufacturers, but the appeal and possibilities are there. The rich history of the AR-15, with the current political climate, means the AR is not about to be replaced anytime soon.

A graphic showing the modular AR-15 sporting rifle system.