By Guy J. Sagi

The border that determines whether a firearm is a carbine VS rifle is a fluid one. A 20″ barrel has been the informal boundary for years. Anything shorter than 20″ is a carbine, and anything longer is a rifle. Except for shotguns, which don’t qualify as either.

The 20” definition remains widely accepted, despite a rapidly closing performance gap fueled by advances in gun manufacturing and cartridge design. Both still present distinct advantages and drawbacks. Which one is best depends on your intended use. A look at how carbines came about illustrates their benefits, some unobtainable in an identically chambered rifle.

Carbine VS Rifle: Early Development

Carbine design has come a long way from tube-fed lever guns (top), to modern magazine-fed semi-autos (bottom).

Precisely where the English word “carbine” originated is still a matter of scholarly debate. The consensus has it evolving from the French term for cavalry—carabiniers.

The background hints at the nimble handling inherent in a carbine. Soldiers on horseback reloading long-barreled muzzleloaders were out of the fight for too long. Have you ever tried to pour powder and stuff bullets from a saddle? It’s not easy.

Is Shorter… Better?

Shorter barrels were a common solution to the horseback problem. It seems the Germans were the first to use them with their arquebus firearms in the 16th century. A better-known example is the short Carbine Model 1793 used during the French Revolutionary War. This .54-caliber wore a 16-inch barrel instead of the 25 1/2-incher on infantry-standard versions.

Gunpowder has less time to burn in a shorter barrel, so velocity and stopping power decrease. Its shorter sighting radius also compromised a shooter’s precision. This limited the designs to effective distances shorter than guns carried by most ground-borne troops.

Then came the Spencer Carbine of Civil War fame, also designed with cavalry in mind. The repeater held seven cartridges and earned respect on both sides of the skirmish line despite appearing later in the war against the states.

Pistol-caliber carbines are a popular topic right now but hardly new. More than 100 years ago, settlers headed west carried short-barreled lever actions and identically chambered revolvers. Even with their reduced effective range and compromise in performance, Carbines remained popular. During World War II, an unusual catalyst forever cemented the term into the American lexicon.

The Carbine Goes Mainstream

David Marshall ‘Carbine’ Williams with General Douglas MacArthur, circa 1950s. (Credit: ncdcr.gov)

After a raid on his moonshine operation left a North Carolina deputy dead, David Marshall Williams pled guilty to second-degree murder in 1921. His three workers claimed they didn’t launch the deadly shots from the forest. One later admitted (in a separate trial) that he was the shooter, not Williams. Regardless, Williams received a 30-year prison sentence.

Carbine Williams: Creative Outlaw

While he served time, the warden and guards noted Williams’ mechanical aptitude. He soon found himself in the tool shop, repairing broken items and handcrafting others. In time, he began working on the facility’s guns.

Using mechanical drawing supplies his mother provided, Williams developed several innovative firearm operation systems, including the short-stroke gas piston. Good behavior, plus a campaign including the endorsement of the deputy’s widow, led the governor to commute his sentence in 1927.

His release came in 1929, and he immediately opened shop in Godwin, North Carolina. He polished his designs, filed several patents, and worked on projects with Colt, Remington, and the Department of Defense.

Birth Of The M1 Carbine

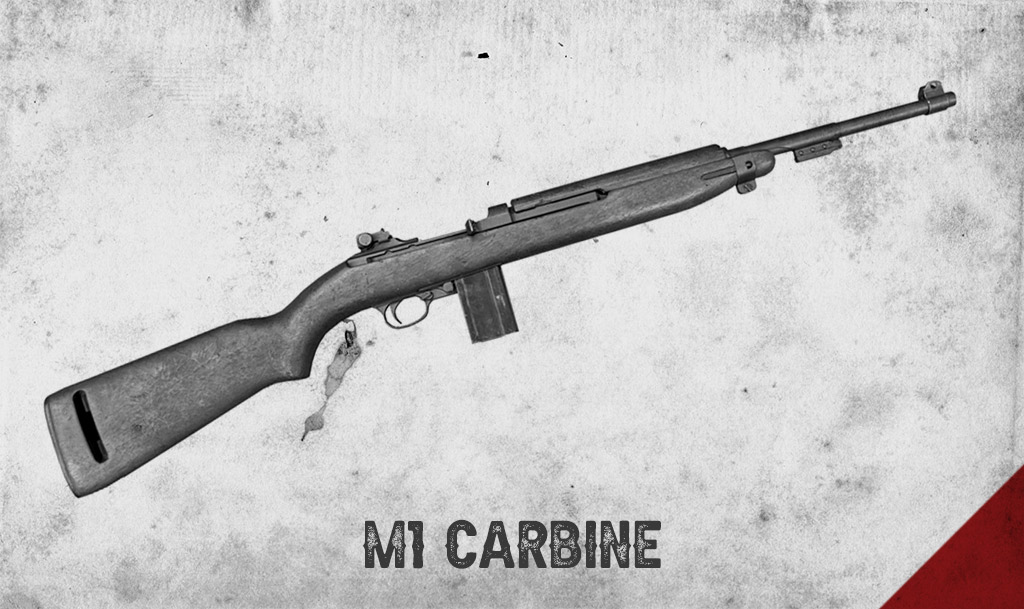

Winchester hired Williams in 1939, a move that would launch him to celebrity status. He and the company’s team designed a 16-inch-barreled semi-automatic that saw widespread use in World War II. That gun, the M1 Carbine, measured only 35.6 inches overall and weighed 5.2 pounds. The U.S. government issued it to a range of U.S. troops, including airborne, artillery, armored personnel, and others. The gun’s chambering, appropriately enough, was for the .30 Carbine—an all-new cartridge.

There were 6.1 million M1 Carbines manufactured by the United States during the war—more than any other small arm our troops fielded. By VJ Day, the gun’s status bordered on legendary. It unofficially earned that title in 1952, when the movie “Carbine Williams” hit silver screens nationwide. Hollywood star Jimmy Stewart played the leading role of Williams in the film.

The term has been a hot topic lately, too. This is thanks to U.S. forces shrinking the length of their standard-issue rifle barrels to the 14.5-inch versions worn by M4 Carbines. That change, more than any other, highlights the benefits they offer.

Carbine VS Rifle: Carbine Advantages

The M1 Carbine saw plenty of action during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

Reduced length and lighter weight make a carbine nimbler in tight spaces, like the close quarters battling so common in Iraq. There’s no long, clunky barrel to hang up on doors or prematurely print a position.

When hunting fast quarry and in shooting action sports, carbines get on target faster. Their reduced weight is a huge benefit if long hauls are on an opening-day schedule. If you’re clambering up to a tree stand, traveling, or if space is tight in the gun safe, a carbine’s smaller profile is a plus. Today, they’re also available in dozens of chamberings.

Carbine Disadvantages

As the global war on terrorism spilled into Afghanistan, engagement distances stretched. What was once primarily a house-clearing affair turned into ridgeline-to-ridgeline fighting. The performance of the 5.56 NATO cartridge was dismal, and those short barrels only worsened it. As a remedy for the problem, the U.S. military brought the fleet of mothballed M14s chambered in 7.62 NATO back into service. That cartridge is a proven performer, but the fact the guns arrived wearing 22-inch barrels says a lot about the carbine’s main drawback.

Short Barrels, Short Burn

The cartridge’s propellant may not have enough time to burn completely in an abbreviated barrel. When that happens, the bullet’s velocity reduces, drop and wind drift increase, and downrange energy suffers. Hit a target slowly enough, and the projectile may also fail to expand.

As for how much it compromises performance, dozens of efforts have tried determining velocity loss as barrel length shrinks. Most subscribe to the 50 fps/inch generality. Other studies found it can run anywhere from 10 to a staggering 200 fps, depending on ammunition, chambering, and the individual gun.

Those unburned particles can also light up the moment they escape the muzzle. Flash hiders remedy the problem, but if you’re shooting in low-light conditions, it shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Scientifically Improved Propellants?

A U.S. soldier’s M4 Carbine exhibits muzzle flash when fired in low light. (Credit: Department of Defense)

Manufacturers are now performing miracles with their propellants. The faster-burning powders and ability of modern bullets to upset (expand) at a lower velocity have brought carbine vs. rifle performance closer than ever. Inhibitors in many powder mixes—particularly those designed for self-defense and duty—reduce or eliminate muzzle flash concerns.

Carbine VS Rifle: More Heat, More Recoil

There’s still no remedy for a few of the other drawbacks to a carbine. Less mass means the barrel heats faster than a rifle-length version. It’s not a situation most recreational shooters encounter. Still, if competition or another heavy-volume-of-fire pursuit is your passion, it’s something to consider. Groups can expand, often unpredictably, when barrel temperatures rise.

According to physics, identical cartridges generate identical recoil, regardless of the gun. However, more force reaches a shoulder with a lighter gun, while a heavier one soaks up more. Perceived recoil may increase in a carbine vs. a rifle. Today, semi-automatics like today’s pistol carbines and the M1 reduce recoil by redirecting that energy into cycling.

Sighting Difficulties

It’s also easier for a carbine’s crosshair or iron sights to migrate slightly off target, a concern if you’re shooting long distances. Iron sight drift is a simple byproduct of a shorter sight radius. Crosshair migration results from a lighter gun being more susceptible to shifts in breathing, slight breezes, or your heartbeat.

The Rifle Conundrum

A rifle’s increased weight anchors it more solidly on target and dissipates barrel heat faster. The powder has more time to burn, so the muzzle flash fades. Bullet velocity increases, and sight radius improves. Recoil in even heavy-hitting loads drops appreciably, more so in semi-automatic versions.

Rifles also weigh more and can get clunky depending on barrel length. If your passion is lying prone every weekend to clang steel at 1,000+ yards, 20 inches likely isn’t enough. It’s common for a precision rifle today in long-distance chamberings to wear at least a 26-inch barrel.

Bullets can also reach a target at velocities above the projectile’s optimal performance window. This increases the odds they will pass entirely through a big game animal with little or no expansion—a concern for hunters working thick brush. You can handle that problem with the right bullet choice, but hot loads and 24+-inch barrels are not ideal for short distances.

Carbine VS Rifle: Which One Should I Buy?

A 24″ rifle barrel (with suppressor) is heavier and more difficult to conceal than a standard length carbine.

Gun and ammunition manufacturers continue to blur that 20-inch definition. The boundary smudges further with each improvement in the propellant, bullet design, and new cartridge. There’s no telling where that border truly is today, much less tomorrow.

Using that 20-inch ruler in the gun store or firing line is still safe. Still, the accuracy of today’s 18- and 16-inch CNC machined “carbine-barrels” rivals or surpasses the longer versions of a few years ago. Add a quality scope, some weight, and a bipod or sandbag, and it’s shocking how they stretch the distance.

Carbines are nimble, lightweight, and now widely available in pistol-cartridge chamberings from various firms. They bring a fashionably low-drag look to the firing line, too. On the other hand, the added length and bulk of a rifle don’t quite fit a high-speed profile. But when you want tight groups in the next zip code, you can’t beat it.

So, now that you know the difference between a carbine VS rifle, will you buy one… or both?