By Guy J. Sagi

The spiralled grooves and lands inside a firearm barrel—rifling—force a projectile to rotate as it travels from breech to muzzle. The spin continues upon exit, improves in-flight stability and enhances downrange accuracy. The critical role it plays is undeniable, although it can be particularly confusing for AR-15 owners interested in maximizing performance. Here are some barrel twist rate facts any enthusiast should consider.

Twist Rate Explained

Bullet weight and length factor into the performance of a projectile leaving a gun barrel with a specific twist rate.

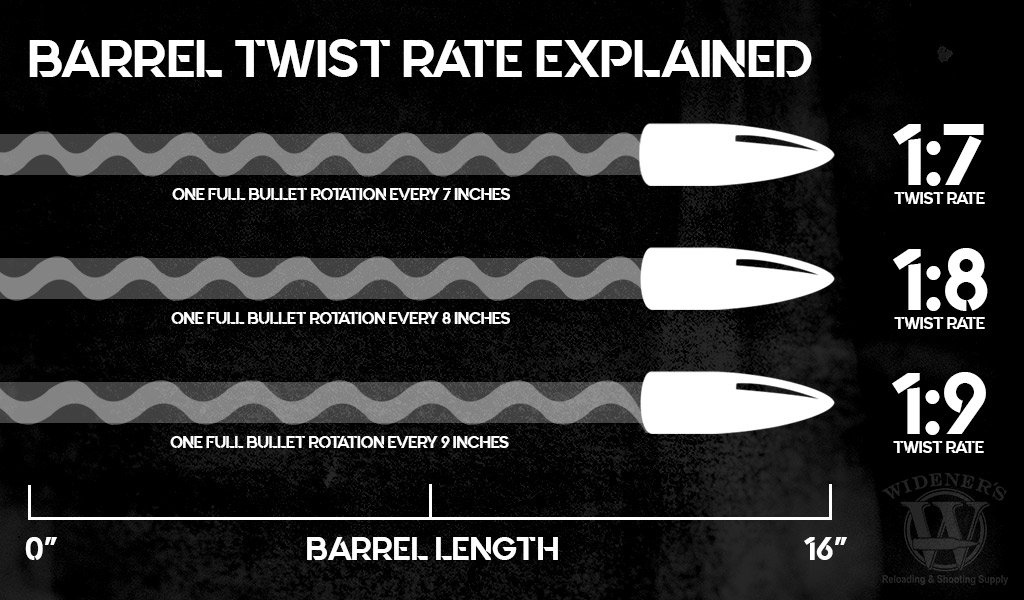

Industrywide shorthand, expressed as 1:7, 1:8, etc., describes gun-barrel rifling rate. The first figure indicates one full rotation of the bullet, followed by the number of barrel-travel inches (in the United States, anyway) required for its completion.

A 1:7 twist means the bullet turns a full 360 degrees every seven inches of barrel. Nine inches of travel for each rotation gives the barrel a 1:9 rifling rate. Some European manufacturers indicate distance in metric units, usually centimeters. Companies routinely report the barrel twist rate information in their documentation and some stamp it onto their barrels.

Similar, Not Always Equal

All rifling imparts a spin on the bullet before it leaves the gun, but the way it gets the job done is not always identical. The designs, however, share the basics—lands, the raised portions of that interior spiral pattern, and the grooves in between.

Lands in traditional rifling are rectangular in shape, with angles at the side that measure at or close to 90 degrees. Polygonal rifling, which is particularly popular in handguns, uses a smoother, less-perpendicular transition into its grooves, reducing the corner “depth” where fouling likes to hide. It’s an advantage for high-volume shooters. There’s also a new generation of rifle barrels that harness a gentle blend of both rifling types, and many produce excellent accuracy at distance.

Does Spin Direction Matter?

Even the rifling’s direction of rotation varies from manufacturer to manufacturer. Some companies build barrels to force bullets to exit with a clockwise spin, others the opposite direction (usually described as right- or left-hand rotation). Accuracy is the same in both, although bullets at extreme distance experience “spin drift,” in which a bullet with clockwise rotation drifts slightly to the right. Counterclockwise projectiles veer minutely left. Bear in mind, environmental factors, shooter skill and firearm maintenance are the overwhelming factors when it comes to accuracy, not a flavor of physics rarely (if ever) visible at the firing line.

You can also find firearm barrels with a different number of grooves, although even that doesn’t affect practical accuracy in modern firearms. Fewer grooves mean bigger, beefier and stronger lands that last longer and are easier to clean, according to some. Others swear less than five grooves compromises the gas seal. Even if it does, it won’t vary and affect the ability to hit the bullseye once the firearm is zeroed.

There’s even debate over whether the number of grooves and corresponding lands are ideally odd or even. Again, opinions vary. Conventional wisdom claims a land count divisible by two exerts pressure on directly opposing sides of a bullet, enough to occasionally deform their streamlined profile before reaching the muzzle. Today, however, manufacturers have created precision barrels with a history of performance in odd and even land-count varieties.

Do The Twist

There’s even a gain-twist (progressive) design in which the rifle’s spiral tightens toward the muzzle. The approach theoretically minimizes the effect of spindrift and some long-distance shooters claim it increases bullet velocity. Early Colts used in the Civil War had progressive rifling, although it’s not available on commercial firearms today—it’s too time-consuming and expensive to produce. A few high-end custom shops still offer it in their barrels and the approach remains hard at work with the U.S. Military, including in the 30 mm Gatling guns mounted on the A10 Warthog.

Regardless of the manufacturer or design, any barrel coming off the assembly line today—with proper care—will be extremely accurate with the right bullet and load. Finding that barrel twist rate combination is key, though, and a basic understanding of rifling’s role in accuracy helps.

How Rifling Works

Looking down the barrel at the rifling of a 16″ AR-15 semi-automatic rifle.

Rifling causes a projectile to spin, but there’s an underappreciated balancing act of science and metallurgy at work. To harness energy released as a cartridge’s propellant burns, the bullet maintains a good seal against the groove walls—all of them. However, the lands rise slightly, minutely intruding into the bore. To glide past them, some of the bullet’s outer material moves, without shaving at each contact point. It’s during that process that the rifling is “engaged,” and rotation begins at the prescribed rate.

Recovered bullets the show scars created during the process—something experts call “engraving.” They’re not as attractive as the embellishment on watches presented to employees retiring after decades of service, but the markings made to a projectile are unique to the barrel it left, an invaluable forensic fingerprint.

That fact alone is indisputable proof that no two firearm barrels are quite the same, even with today’s CNC precision. One may have followed the other off the assembly line and share identical specs, but they and their rifling are fraternal twins, not identical.

AR Barrel Rifling

The most common barrel twist rates for modern rifles are ratios of 1:7, 1:8 and 1:9.

Today the most common rates of rifling in AR-15s are 1:7, 1:8 and 1:9. When Eugene Stoner designed the M16 he originally made things much slower—1 complete turn every 14 inches, with four grooves, to be precise.

Good luck finding that in modern semi-autos chambered for .223 Remington ammo or 5.56 NATO. A few early Colt ARs featured 1:12 and some bolt-actions designed for light, varmint-hunting bullets still feature low twist rates. Barrels in standard M4s fielded by the U.S. Military are currently rifled at 1:7.

Accuracy: Heavy Fast, Light Slow

Bullet weight plays a huge role in all this. Accuracy and bullet preference vary slightly in each firearm, but most agree heavy bullets require a faster rate of twist to remain stable in flight. It’s a time-proven statement, although a study conducted by the U.S. Army in early 1986 indicates the sage advice may cite the wrong projectile spec.

The government research determined the then-standard 62-grain bullet was most accurate when delivered from M16 test barrels with 1:9 rifling. Unfortunately, tracer rounds were longer. They added 1.7 grains to their payload and became largely unstable downrange when delivered from the same guns. Further testing determined 1:8 was also good for the ball ammo. But it apparently did not display enough of an improvement to unseat 1:7.

Weight undoubtedly played a role in the tracer inaccuracy. The results lend support to the belief that bullet length is the primary determining factor in the optimum rifling rate. Which barrel twist rate theory you subscribe to doesn’t matter right now. Today’s longer bullets weigh more than shorter ones of the same caliber and design. As manufacturers introduce different alloys and fine-tune core materials that can change.

Rifling For Common AR-15 Rifles

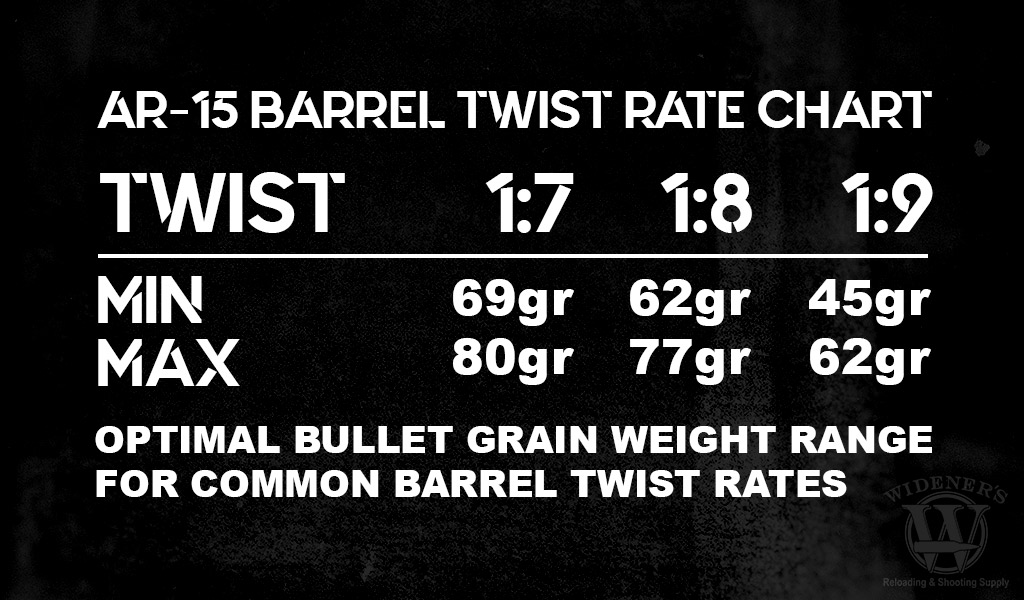

Higher number twist rates perform better with lighter grain bullets, while lower number twist rates perform better with heavier grain bullets.

Common wisdom for 5.56 NATO and .223 Rem. indicates those barrels with a rate of rifling at 1:9 or slower (1:10 etc.), in general, perform best with lighter bullets—60 grains or less. If you’re looking for a general-purpose, workmanlike utility player that pleasantly gobbles up anything thrown its way, 1:8 is a solid choice. Heavier bullets perform best from barrels rifled at 1:7. Those 75-grain loads and up are very comfortable at this rate.

Too much rotation on a light (shorter) bullet and it can suffer out-of-control “overspin” downrange. Those longer heavyweights require more “twist” to initiate the motion and remain stable at distance.

Why Experiment With Twist Rate?

If you want the best performance from your rifle, you’ll need to test the ammo needed for your barrel’s twist rate.

Accurately predicting bullet design and optimal weight for a firearm when armed only with specifications and rifling rate is impossible. It doesn’t matter expert you consult. Odds are good the above generalities will come close, but slight differences in manufacturing render blanket advice from afar mere suggestion.

Barrel length, profile and maintenance also play undeniable roles. There’s no shortage of well-documented rifles that simply defy all the rules. Outperforming the manufactured “conformists” that came out of the factory the very same day.

You’ll never know your AR’s true potential until you experiment with barrel twist rate. Yes, begin with a couple loads that fall squarely within the above-prescribed diet for your firearm’s rifling. Bring at least one box of ammo with heavier bullets and another with lighter ones, though. Spend some quality time at the firing line and you may be surprised at the performance you discover.