Any 1950’s kid who ever donned a cowboy hat and strapped on a six-shooter cap pistol remembers the theme song to The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp. It was a TV show that ran (in glorious black and white) from 1955 to 1961. Starring the cool and handsome Hugh O’Brian, the series traced Earp’s career as a deputy town marshal in Ellsworth, Kansas, all the way to his time in Tombstone, Arizona, and the infamous gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

While not lasting as many years as either of them, Wyatt Earp premiered before both Gunsmoke and Cheyenne, providing three shoot-em-up TV westerns to “enrich” the minds of all those impressionable adolescents during the 1950s.

“Wyatt Earp, Wyatt Earp,

Brave, courageous, and bold.

Long live his fame, and long live his glory

And long may his story be told.”

— Chorus to the theme song for The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp

For those who loved those shows—and they had huge followings—these tales of the old West served as a history lesson and shaped their early philosophies: good would always triumph over evil, and justice would be meted out fairly.

Television Mythology

While both Matt Dillon of Gunsmoke and Cheyenne Bodie were larger-than-life fictional characters, Wyatt Earp was a real-life historical figure. And although no one explicitly claimed biographical accuracy for the show, the kids (mostly boys) who were glued to the tube once a week believed the truth resided in every episode.

For starters, who will ever forget Wyatt’s Colt Buntline Special, a .45-caliber revolver with a 12-inch barrel that the marshal used to subdue the bad guys in Dodge City and Tombstone. But how closely is this impressive weapon linked to the real Wyatt Earp? And are there other areas of this legendary figure that are more myth than fact?

Below is what historians believe is the true story:

The Early Years

Wyatt Earp was born in Illinois in 1848, the fourth of eight children. His brothers Virgil (1843) and Morgan (1851) would play important roles throughout Wyatt’s life. Wyatt would move around frequently during his life, and in 1869, his family would move again, this time landing in Lamar, Missouri. Here, Earp met and married 20-year-old Urilla Sutherland. But his life would take a downward spiral following her death from typhoid fever in 1870. She was about to deliver their first child when she died suddenly

Earp had several run-ins with the law after Urilla’s passing, including charges of embezzlement and horse stealing, but he was never tried for either of these. After settling in Peoria, Illinois, in the early 1870s, he was arrested for offenses connected to his involvement with brothels. And after moving to Kansas in 1874, he was once again detained and fined multiple times while he worked as a bouncer in various houses of ill-repute.

On one such occasion, Sally Heckell, a prostitute calling herself his wife, was arrested with Earp. The two would subsequently move to Wichita, Kansas, in 1874 and continue operating a brothel until the middle of 1876. While in Wichita, Earp would become a deputy marshal, but a fistfight with a former marshal would end that stint. One of his brothers had just opened a brothel in Dodge City, and Wyatt left Wichita, without Sally, to join him.

The Legend Of Wyatt Earp

Long before he became a US Marshal, Wyatt Earp had a knack for ending up on the wrong side of the law.

By the time Wyatt reunited with his brother in Dodge City, it had become a terminal for cattle drives from Texas. Although he had been appointed assistant marshal, the restless Earp left after a few months, ending up in the gold-rush boomtown of Deadwood in the Dakota Territory. He spent the winter of 1876-1877 hauling firewood there.

But by the spring of 1877, Wyatt Earp was back in Dodge City as a police officer. Later that same year, he received a temporary commission as deputy U.S. Marshal to follow and apprehend an outlaw named Dave Rudabaugh. The pursuit would take him to the Texas town of Fort Griffin, where he met gambler Doc Holliday. The chance meeting would lead to a lifetime friendship.

Dodge City

On his return to Dodge City in 1878, Earp was once again appointed assistant marshal. He met another famous gambler, Bat Masterson, and a prostitute named Mattie Blaylock during this time. Blaylock would become his common-law wife and remain so until 1881.

In the early hours of July 26, 1878, a group of drunken cowboys began shooting their guns crazily. Three shots would enter Dodge City’s Comique Theater, causing patrons to seek cover. Marshal Earp and now-policeman Bat Masterson responded, opening fire on the fleeing cowboys.

One of the horsemen, George Hoyt, was wounded and fell off his horse after riding out of town. The local newspaper reported that Hoyt had developed gangrene and died three weeks later. However, many years later, Earp would tell his biographer, a writer named Stuart Lake, that he had seen Hoyt, illuminated by the morning horizon, and fired a shot that killed him instantly.

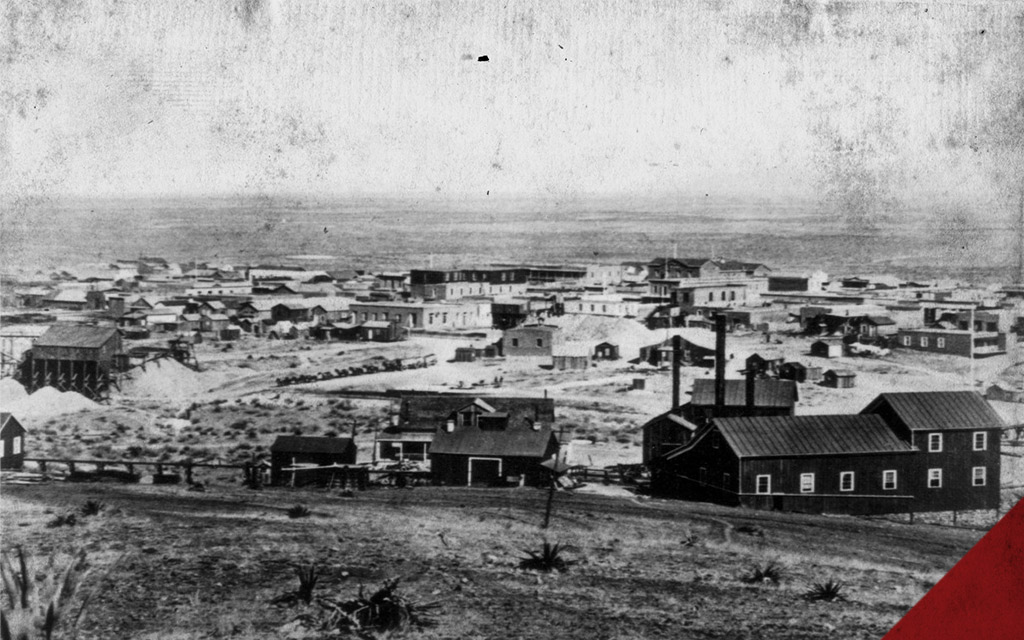

Tombstone, Arizona

Tombstone, Arizona was a rough Old West town in the 1800s.

The bad blood that would culminate in actual bloodshed near the O.K. Corral began in the summer of 1880. Army Captain Joseph Hurst requested help from Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp in finding six Army mules stolen from Fort Rucker, Arizona.

With help from his brothers Wyatt and Morgan, the men found the mules at the ranch of Frank and Tom McLaury. The McLaurys were “Cowboys,” a term that referred to a group of outlaws in the area. When the cowboys refused to return the mules and made overt threats to Hurst and the Earps, the seeds of violence were planted and began to grow.

The tension between the Earps and the Cowboys reached a high point on October 26, 1881. Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury, having been pistol-whipped by the Earps earlier in the day, were looking for revenge by the afternoon. They gathered on Fremont Street, near the O.K. Corral. Soon, the Earps and Doc Holliday walked down to meet them.

Showdown At The O.K. Corral

Much has been written, and several movies have reenacted the thirty-second gunfight. What is known for sure is that when it was over, Frank McLaury had been killed instantly. His brother Tom and Billy Clanton died within an hour. Virgil and Morgan Earp, along with Doc Holliday, were wounded. And Wyatt Earp and Ike Clanton survived unscathed.

With so many guns firing almost simultaneously amid utter confusion, it’s unclear whether Wyatt shot any of the Cowboys. However, most historians agree that Wyatt was not the central figure in the gunfight and that the fact he was not injured in that and subsequent fights only added to his mystique.

Wyatt Earp’s Gun

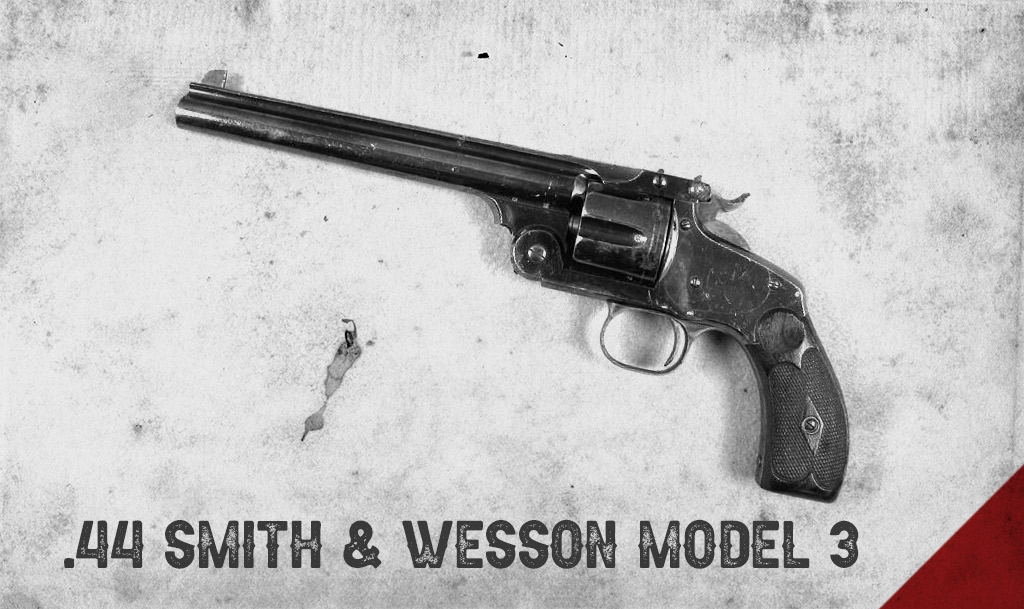

Wyatt claimed to be armed with a .44 Smith & Wesson Model 3 at the O.K. Corral shootout.

For all its notoriety, very little is known about the weapons used during the gunfight. Only two guns—both .44-40 Colt Single-Action Army revolvers—have been identified as belonging to Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury. They were retrieved and recorded immediately after the fight.

While no one knows for sure what Wyatt Earp used in the gunfight, there is little doubt that it was not a Colt Buntline Special (it’s even doubtful that such a gun ever existed). As a matter of fact, most Old West historians now believe that it wasn’t a Colt pistol at all. Wyatt Earp reportedly told his biographer, Stuart Lake, that he was armed with a .44 Smith & Wesson Model 3 during that notorious shootout. However, considering all the dubious claims Earp made to his biographer during his last years, that may or may not be accurate.

A Man Of Many Hats

Wyatt Earp wore many hats in many places during his adventurous life. He passed away in Los Angeles in 1929 at the age of 80. While the gunfight helped define Wyatt as a courageous lawman and folk hero, it was Lake’s best-selling, albeit highly fictionalized, biography Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal that cemented his legacy. The movies and TV shows based on the book would later immortalize him.

Over 90 years after his death, he still has many devoted followers and a few detractors. Wyatt Earp was a complex and polarizing individual who defied being stereotyped. On the one hand, he “blurred the boundaries of law and criminality,” as one PBS documentary claimed, but for those who sprawled on the living room floor and worshipped him on the small screen, he was a brave, courageous, and bold hero whose fame will live forever.