Outspoken. Brilliant. Arrogant. Spiritual. Vulgar. These are just a handful of the adjectives attached to George Patton, all of which described him accurately at one time or another.

A complicated man, Patton was a Christian (Episcopal), yet he often studied the Koran and the Bhagavad Gita. He prayed to a personal God and turned to the Bible for inspiration, but he also believed in reincarnation, asserting that he had lived former lives.

The object of war is not to die for your country but to make the other bastard die for his.”

— General George S. Patton

George Patton would become a high-ranking general and one of the most colorful figures in military history. “Old Blood and Guts,” as some called him, would produce faster results with fewer casualties than any other general during World War II.

George Patton: Aristocratic Beginnings

George Smith Patton Jr. was born in 1885 near Los Angeles, California, into a wealthy and aristocratic family. Patton’s father graduated from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), later becoming a lawyer and the district attorney of Los Angeles County.

His aunt homeschooled George until he was eleven years old. He spent the next six years in a private school and, following that, attended VMI as his father had. At the age of seventeen, he sought and received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Despite having an undiagnosed learning disability early in his life, Patton graduated in the top half of his class at the academy and received a commission as a second lieutenant.

Competing In The 1912 Olympics

George Patton represented the United States, as a pentathlete, at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm. The pentathlon—fencing, riding, swimming, running, and shooting—made its Olympic debut that year. Patton, a 26-year-old Army lieutenant, finished fifth behind four Swedes.

Not surprisingly, Patton became embroiled in a bit of controversy. In the shooting event, he finished 21st because the judges ruled that one of his shots had missed the target. Patton disagreed, claiming that some of the rounds had passed through the same holes. The officials were unconvinced, and Patton missed out on an Olympic medal.

General George Patton’s Guns

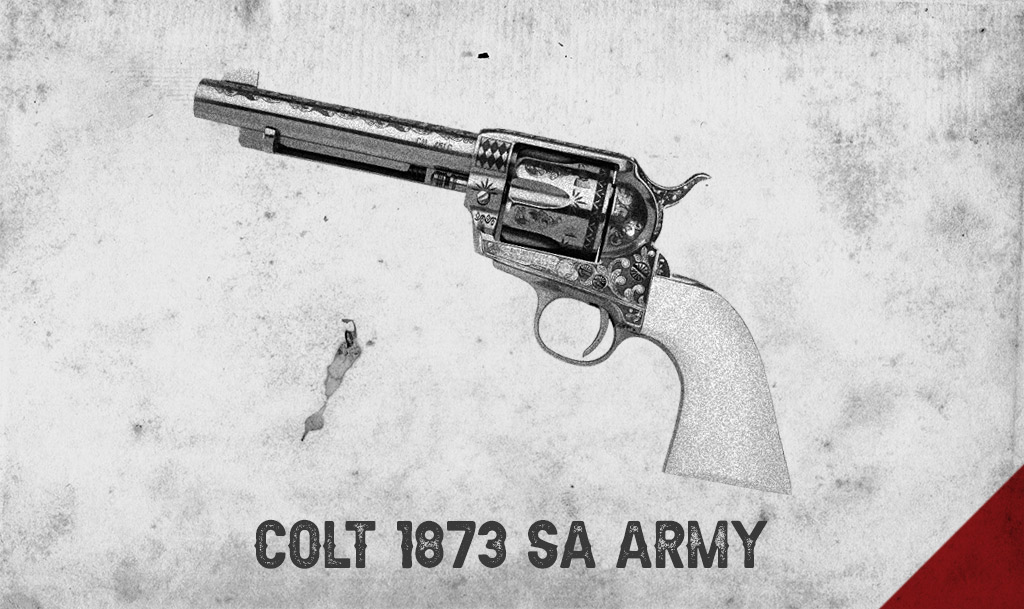

The Colt Single Action Army revolver became the standard-issued pistol of the US Army in 1873.

While on Mexican border patrol in 1915, Lieutenant Patton was wearing his weapon-of-choice, a semi-automatic Colt M1911 M1911 pistol, chambered in .45 ACP, when he visited a local saloon. The pistol discharged accidentally, and Patton decided to replace it.

In its place, he chose an ivory-handled Colt Single Action Army revolver. A sidearm chambered in .45 Long Colt that would become a permanent part of his flamboyant image. Anyone who watched the movie Patton will remember the scene in which a reporter referred to the general’s “pearl-handled” pistols, only to be quickly and sternly corrected.

Patton In World War I

Patton joined the staff of General John J. Pershing after the United States entered World War I. He arrived in Europe as a captain, and within months was promoted to lieutenant colonel. In September of 1918, Patton was wounded near the French town of Cheppy. He had been leading six men and one tank on an attack on a German machine-gun nest.

In a letter to his wife, he described a leg wound. It resulted in a bullet coming out “at the crack of my bottom about two inches to the left of my rectum.” He estimated that it had been fired from fifty meters, so it “made a hole about the size of a (silver) dollar where it came out.”

Colonel Patton received the Distinguished Service Cross. The letter which accompanied the medal stated that Patton had displayed “conspicuous courage, coolness, energy, and intelligence in directing the advance of his brigade.” And it praised him for rallying “a force of disorganized infantry and (leading) it forward, behind the tanks, under heavy machine-gun and artillery fire until he was wounded.”

U.S. Armor For World War II In Europe

Patton was promoted to major general during WWII, giving him command of the 1st Armored Corps of the US Army.

About eight months before the country’s direct involvement in the Second World War, Patton received a promotion to major general. Soon after, he took command of the I Armored Corps and became a well-known symbol of U.S. armor.

General Patton began staging exercises that included over one thousand tanks and other vehicles. He earned a pilot’s license and began observing the vehicles’ movements from the air. These mass maneuvers, many of them in the California desert, continued into the summer of 1942, and his picture was soon on the cover of Life magazine.

George Patton Turns Things Around In North Africa

After another humiliating Allied defeat in the Battle of Kasserine Pass in Tunisia, Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower replaced Major General Lloyd Fredendall, commander of U.S. II Corps, with Patton. Patton quickly turned the demoralized troops into an effective fighting machine. Returning discipline, instilling a fighting spirit, and training relentlessly.

Patton’s effective methods resulted in a victory at the Battle of El Guettar. The first major tactical victory for the Allies against the German army. Under Patton, II Corps forced both the German and Italian armored divisions to retreat.

Patton eventually relinquished command of II Corps to General Omar Bradley. He returned to the I Armored Corps in Casablanca and work on Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily.

The Invasion Of Sicily

Operation Husky began in July of 1943 with 150,000 troops, 3,000 ships, 4,000 aircraft, and 600 tanks. Lieutenant General Patton commanded the American ground forces, and for five weeks, Patton’s army moved toward the northwestern shore of Sicily. Two weeks after the invasion had begun, Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini was deposed and later arrested.

Within days of Mussolini’s arrest, Italian troops were withdrawing from Sicily. Allied soldiers, with Patton and British General Bernard Montgomery in command, had pushed the enemy forces and trapped them in the corner of the island.

While the invasion was progressing, Patton visited the 15th Evacuation Hospital and spotted a soldier sitting on a supply box. When the general asked him why he was in the hospital, the soldier replied, “I guess I just can’t take it.” Patton was incensed, swearing at the soldier and slapping him with his gloves.

A week later, at another hospital, Patton approached a soldier lying on a bed. Once again, Patton asked the man what was wrong. “It’s my nerves,” the soldier said. At which time Patton called him a coward, before hitting him and ordering him to the front line.

When General Eisenhower heard about the incidents, he demanded that Patton apologize publicly to the troops and the two ridiculed soldiers. He obeyed the order.

The Battle Of The Bulge

The “Battle of the Bulge” was the largest and bloodiest single battle fought by the United States during World War II.

British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill called it “the greatest American battle of the war.” Named the Battle of the Bulge because of its appearance on a military map. It began when Adolph Hitler sent more than 200,000 Wehrmacht troops and nearly 1,000 tanks to split the Allied armies and reach the English Channel.

The Germans attacked in the Ardennes Forest, a dense area with few roads in eastern Belgium. Although surrounded and cut off, American soldiers held out near the city of Bastogne. Keeping the Germans away from the roads they had planned on using to stage the offensive.

Gen. Eisenhower ordered Patton’s Third Army to relieve the beleaguered men at Bastogne. And within days, Patton and his tanks arrived at Bastogne and broke the siege. It was reported that the Third Army had “rescued” the isolated soldiers there. However, most of those ground troops who fought the Battle of Bastogne insisted that they hadn’t needed Patton to liberate them.

Untimely Death

After Germany’s surrender, Patton was in trouble for publicly criticizing the Allies’ strict de-Nazification program. In October of 1945, Eisenhower removed him from command of the Third Army. Two months later, General Patton sustained neck and spinal cord injuries in an automobile accident near Mannheim, Germany. Twelve days later, he died from a pulmonary embolism that resulted from the accident. He was only 60 years old.

George Patton: An American Legacy

In its obituary of General Patton, the New York Times called him “one of the most brilliant soldiers in American history.” Using words such as “audacious, unorthodox, and inspiring.” John D. Eisenhower, the son of Dwight Eisenhower, served under Patton and remembered him as both “professional and eccentric” and praised “his total devotion to the military.”

In his review of the book Tragic Hero, by Stanley Hirshson, David Shribman called Patton “a warrior and an American and, more than that, he was an American original.” There is little doubt that George Smith Patton was an original, the likes of whom we are not likely to see anytime soon.