By Guy J. Sagi

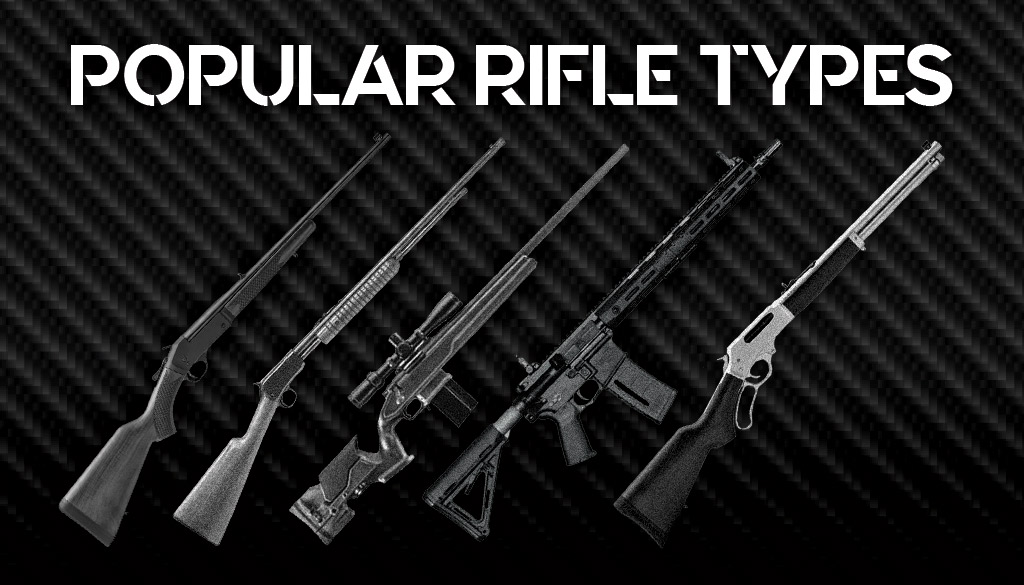

The creativity and engineering prowess poured into today’s rifles may be unlimited, but all firearms fall into distinct categories defined by their method of operation—regardless of cosmetics. Here’s an abbreviated look at the five major types of rifles.

Types Of Rifles

- Break-Action

- Lever Action

- Pump Action

- Bolt Action

- Semi-Auto

Break-Action Basics

The simplicity of the break-action rifle can be a plus for hunters who require large calibers for big game.

Yes, these back-to-basics versions still exist, despite the relative rarity on gun store shelves. They’re reliable, trustworthy, and don’t attract a lot of attention. Most rifles in this category have a single barrel, with a couple of interesting exceptions.

A break-action’s operation is straightforward, simple, and adds a layer of safety when introducing new shooters to the sport. The barrel/chamber rotates down from the receiver assembly—trigger, stock, firing pin, etc.—for removal or insertion of cartridges. When left open this way it all but eliminates any chance of a negligent discharge, even if a branch somehow engages the trigger during a long hike. It also makes it easy to visually determine if the gun is “safe” from a glance.

Multiple Triggers, Multiple Rounds

A hinge makes rotation almost effortless. The barrel and receiver rotate and seat back together after inserting ammunition, although even then the rifle may not be ready to fire. In some cases, hammers need resetting. In others, they do so upon closing, but a safety can automatically engage. Don’t look surprised at the multiple triggers, either. They allow shooters to select the cartridge or shell dispatched with each pull of the respective trigger.

Double-barreled dangerous game rifles chambered in heavy-hitting cartridges—with names that end in Nitro Express, H&H, Rigby, and others—are usually associated with safari hunters and their occasional need to stop rogue elephants. This style, however, can also digest more familiar and less-painful loads. There’s no denying the style is timeless.

Drillings, sometimes called combination guns, have multiple barrels that are not identical in caliber. They are extremely popular in Europe, although the addiction isn’t quite as catching in the states. Expect at least one barrel—sometimes two—to digest shotshells, but another will chamber rimfire or centerfire rifle cartridges. The attraction is undeniable for small-game hunting.

Lever Action Rifles

Henry makes a variety of different lever-action rifles with more caliber options than you’d expect.

Make no mistake about it, lever-action rifles are far more complicated machines than they appear. Done right, all the parts work in unfailing concert to provide an effective, yet hard-to-beat nostalgic experience. Winchester “won the West” with lever-action styles in the 1800s, but modern manufacturing continues to produce amazing specimens of this species.

How Does a Lever Action Work? Operation is simple. A large loop under the trigger and stock rotates down, away from the rifle. That opens the action while extracting and ejecting empty or loaded cartridges from the chamber. Reverse the motion and the bolt glides forward, picks up any ammo stored in the magazine below and seats it properly into the chamber, locking the thing tightly in preparation for the next shot.

Lever Action Tubular Mags

A tube-shaped magazine runs beneath and parallel to the barrel. Cartridge-carrying capacity varies by model and chambering, but in all cases the ammo lines up single file for feeding—bullet nose touching the base (primer) of the cartridge in front. That makes selecting the right ammo, particularly a centerfire version, a critical safety consideration. Pointed bullets not designed for the duty can strike the primer ahead during recoil with enough authority to touch off a round.

Hornady’s LEVEREvolution is a good example of a safe-to-use modern load with polymer tips that improve exterior ballistics. For nostalgic hunters or wannabe lawmen, the lever action is a prized and very common type of rifle among modern shooters. As a result, Widener’s offers a wide variety in .30-30 Win. ammo to keep those rifles fed.

Pump Action—Hunting, Target Shooting

The pump-action Winchester Model 62A rifle is a classic rimfire plinker.

Shotgun versions get the glory while pump-action rifles—sometimes referred to as slide-action—live in relative anonymity. Some timeless favorites use this method of operation, including the rimfire-digesting Winchester Model 62 and Remington Model 12. The Remington 760 and 7600 centerfires continue to be popular options, with the latter still in production.

A shooter slides this rifle’s fore-end—sometimes called a forestock—back and forth during operation, with spent casings extracted and ejected during the rearward cycle. Pushing it forward again picks up a fresh cartridge from the magazine, chambers it, and locks things pressure-tight at the full-forward position. It’s now ready to fire and repeat the process.

Magazine styles vary, from drop boxes to tubular versions. The latter, naturally, requires the same lever-action attention to cartridge choice.

Bolt Action Rifles

The Remington Model 700 is a bolt-action rifle that comes in a variety of centerfire calibers.

Instead of a separate mechanism forcing the bolt to extract, eject, pick up and chamber a round from a “remote” location, bolt-action rifles employ a much simpler handle. It’s short, direct, and about as close to unfailing break-action simplicity as you can get. Even after more than 100 years of service, the bolt action is still one of the most popular rifle types.

Push it forward and the bolt picks up a fresh cartridge and chambers it, ready to shoot. After a shot, bring it back, and the empty brass extracts and finally ejects. In most cases, the bolt rotates slightly at the forwardmost end to attain full lockup, where it contains all pressure properly in the chamber. It requires an identically slight twist to unlock and start the rearward stroke. There are, however, a rare few bolt actions termed “straight pull” that don’t require that extra motion.

Magazines for Bolt Actions

Most bolt actions have magazines. Capacity varies by model and cartridges the rifle digests. Their configurations are often different, with some of them removable from the bottom for easy reloading. Others are a permanent fixture, and their ammo is either stuffed f from directly above or below after opening the bottom metal.

Bolt-action, single-shot rifles also exist. They are also a great place to introduce newcomers to the sport because removing the bolt provides the same unfailing safe-for-travel configuration as break actions. Its “made safe” status is also obvious.

Popular Types of Rifles: Semi-Autos

The Knights Armament Company SR-15 E3 Mod 2 Semi-Auto Rifle chambered in 5.56.

Modern semi-automatic rifle bolt carrier groups cycle back and forth in the same fashion as their bolt-action siblings. The difference is in their ability to capture energy or gas generated during each shot and repurpose it to perform that chore without a shooter ever working a lever, bolt or pump. The cycling is fast and efficient, but each shot requires a separate trigger squeeze.

Semi-automatic rifle operating systems vary considerably in design. Even modern sporting rifles come in different varieties, including traditional gas impingement or the slightly later-arriving piston-driven system. Other guns get the work done for you by tapping into the energy of recoil or by the blowback mechanism typically found in rimfires.

Magazine capacities vary in nearly all the models, from hunting-friendly five- and six-rounders, up to the 30 or more ideal for competition and lengthy range sessions. This variety of options makes the semi-auto one of the most popular rifle types. A visit to your favorite gun store makes it obvious looks, accessories, and features are virtually limitless.

Summing It Up

Modern ammunition options are the same—improved and better than ever. There’s never been a better time to dust off that break action that’s been collecting dust in the closet, or empty a few mags at the range – no matter which variety of the types of rifles sit in your gun cabinet.