Basics Needed for Reloading

By Guy J. Sagi

There are three good reasons firearm enthusiasts should consider reloading ammunition. First and foremost is the fact it can save a significant amount of money for medium- to high-volume shooters.

Then there’s the finicky nature of guns when it comes to precision at long distance. Tiny tweaks in the magical mix of powder, primer, and bullet—usually not available in factory loads—can make a dramatic difference downrange.

Why Should I Reload?

Do you like to shoot and save money? Reloading may be the best option to keep your cash and stack your brass.

Writers often cite the third reloading advantage as the ultimate solution for high demand during an approaching zombie apocalypse or “Red Dawn” scenario. The tongue-in-cheek mentions don’t do justice to the impact routine and periodic material shortages have on ammunition availability and price.

Some of the industry’s finest appeared during such times, including Speer in 1943—when World War II made stateside bullets hard to find. Joyce Hornady was an early partner in that venture, creating bullet jackets from spent rimfire brass. Sierra Bullets began bolstering supplies when civilian sources were still scarce in 1947. Hornady branched out to form his own company two years later.

More recently, 5.56 NATO casings and 9mm rose significantly in price and were periodically hard to find during the ongoing Global War on Terrorism. And, politics aside, it’s hard to predict where raw material tariffs will lead.

There is an initial investment in equipment to begin reloading, although the odds are good it’s less expensive than you think. Here’s a look at the bare-bones essentials required to start.

The Reloading Cookbook

The Hornady Handbook Of Cartridge Reloading is a great reference book to use for reloading ammo.

At least one reloading manual published or endorsed by a reputable company is mandatory. Internet experts may recommend or brag about pushing the limits, but safety is first and foremost in all things firearm—including cartridges. Some firms publish detailed information and updates on their websites, which is a great resource, but having a reference handy and in writing is always the best approach.

Businesses in the industry know and adhere to the cartridge’s safe pressure limitations and specifications, as prescribed by the Sporting Arms Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute (SAAMI). Experts test the “recipes” extensively and ensure proper operation in a variety of pressure-affecting conditions, like summer’s scalding heat. Their expertise is both reassuring and invaluable as you begin handloading.

Keep it Clean

Dirty brass? Clean it fast with an ammo tumbler loaded with crushed walnut shells.

Spent casings (brass) get dirty. They collect dust and dirt at the range like magnets and there’s always a minute amount of powder residue that remains. You don’t want any of that contamination remaining when you reload.

Case cleaners are inexpensive, even ultrasonic versions that scrub brass clean enough to make mom proud. If you insist on a shiny, fresh-from-the-factory gleam, add a tumbler.

Consult the cookbook for proper inspection procedures and danger signs that indicate the casing needs discarding. When in doubt, throw it away. Fresh casings are the best bet, can be used multiple times and are not expensive.

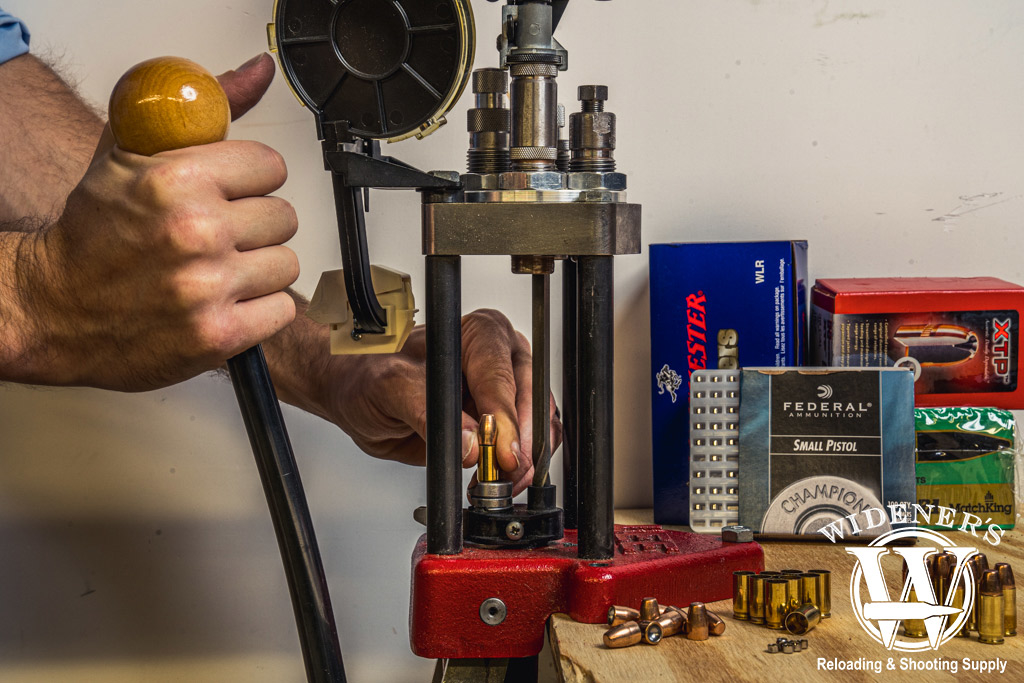

Single-Stage Press

A single-stage reloading press is the least expensive way to begin this cost-saving hobby. There are more advanced models that can churn out higher volumes with less effort, but the knowledge gained working this simple and space-saving tool is invaluable.

A single-stage reloading press has a long lever to provide enough mechanical advantage to easily force dies over, through and around a casing as they perform a variety of tasks. There are several steps, each completed one at a time—hence the “single-stage” name. Most require threading of a task-specific die into the machine. The press holds the case securely during the processes.

Progressive Press

For enthusiasts who shoot in competition or plink through a lot of ammo, processing hundreds of cartridges can be time-consuming on single-stage reloaders. Progressive presses are the answer.

Progressive presses can perform multiple tasks with each crank of the handle and come in two different styles. Manual-index versions require manual rotation of the shell plate to the next position, where the casing properly aligns for another process. Auto-index models have their shell plate turn automatically with each press of the handle.

It sounds slow, except many versions feature plates that anchor multiple casings. Each undergo a separate step with every pull of the crank. The clever approach makes it possible to churn out hundreds of cartridges an hour (depending on model).

Bear in mind, however, it is always best to postpone graduation to a progressive press until gaining a full appreciation of reloading’s precision and requisite attention to detail. Time behind a single-stage press is the best way to acquire that knowledge.

Even if you upgrade, the odds are good you’ll continue to use the basic equipment you’ve collected. Tolerances still need checking. Powder charges require confirmation and there are those small-volume tests you’ll want to run whenever a powder company endorses a new “recipe.” Nearly every experienced high-volume reloader who has upgraded keeps a single-stage press mounted proudly on their bench. It’s not there for nostalgic reasons.

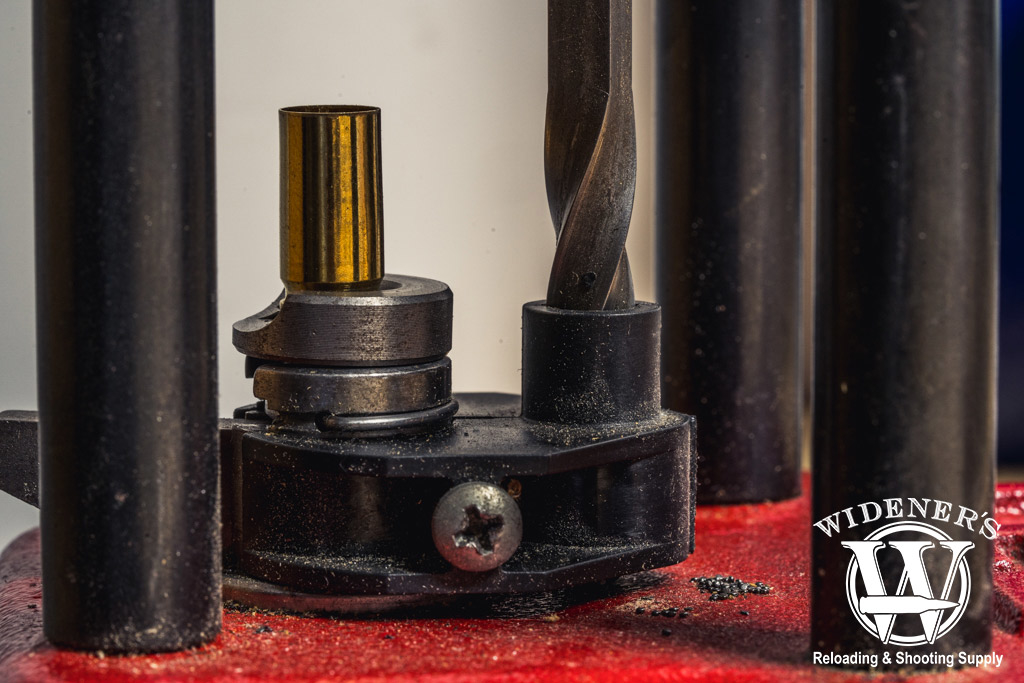

Reloading Method In Brief

Succesful reloading is a matter of following the correct formula and steps to achieve consistent results.

A decapping pin on the press pushes out the centerfire’s primer. A resizing die brings the malleable metal back to proper size and shape. Other dies safely seat a fresh primer, gently expand the case mouth to accept a bullet, seat the new projectile and add a crimp to secure it. Expanding dies are often hollow, saving time by allowing the gunpowder charge to drop in after its insertion.

Those are the required press steps for straight-walled handgun ammo, but the tapered bottleneck casings on most rifle cartridges require a few different tools. During resizing casings stretch slightly. A case trimmer removes the excess. Then a deburring and chambering tool removes the resulting ragged edges. Those long cases aren’t die friendly without lube, either, which adds another modest investment before you begin.

You will need a proper sized set of dies for each cartridge you reload. You will also need a shell holder for the reloader to anchor the case during processing. Some dies do double duty, but consult with respective manufacturers before purchase.

Weighing In

Companies have exhaustively tested the amount of powder safe to use in each cartridge. Follow that advice, implicitly, and to streamline the process during reloading consider investing in a powder dispenser. Once set to the proper amount propellant is dispensed with every turn of the handle.

Add a layer of safety by using a separate and accurate scale to ensure calibration is correct. Check often. Too heavy of a charge spells trouble. The measurements, however, are precise and in units much smaller than in common use—measured in grains, not even ounces—so the kitchen scale is not going to work.

You’ll also need a supply of correct primers for specific reloads. Not all are the same. Consult the manual and, while you’re at it, leave it open to the proper page while you’re cranking out ammo.

Reloading Accessories

A good pair of calipers can do more than find reloading errors, they can actually save your life.

Calipers are critical. They check bullet seating and resultant overall length of a cartridge. It’s an essential consideration to avoid over-pressure and ensure that gun digests your reloads reliably. Trust me, you don’t want to end up in a viral internet video because you didn’t take the time to check your reloads with a caliper.

Ammo likes to roll off on a bench rest, and it does the same on workshop tables. Reloading blocks have tidy compartments to hold casings in various stages of reloading, without risk of spilling propellant or suffering inadvertent knocks. They are an underrated and convenient timesaver.

Succesful Reloading Tips

Once you get the hang of it, reloading is surprisingly simple. It is a time commitment, but it’s one you are sure to enjoy as you gain valuable ballistic knowledge and know-how.

A few of these tips may help you achieve success with your first time reloading.

- Safety first, always visually inspect your workspace for potential hazards before reloading.

- An uncluttered workspace empty of outside distractions is important.

- Reloading is straightforward, but undivided attention to detail is mandatory for safety.

- Fired brass is cheap, make sure to clean it, check it for defects and lubricate.

- New brass requires more work to reload than fired brass, lubrication is your friend.

- Buying brass that has already been primed is a faster way to reload.

- When loading powder, check your caliber and measure twice.

- Measure your seated rounds with a caliper, if you can’t chamber it, don’t shoot it.

- Store your reloads in a cool, dry place.

- If your reloaded ammo is shooting low, reduce the load. If it’s shooting high, increase it.

The inventory needed for reloading may sound overwhelming, but there are many affordable kits available that come with all the required supplies. If you shoot a lot, they’ll pay for themselves in a couple of range sessions. And, if you’re more about long-distance connections, you may be surprised just how accurate that old beater is once you dial into that reloading manual’s magic recipe.