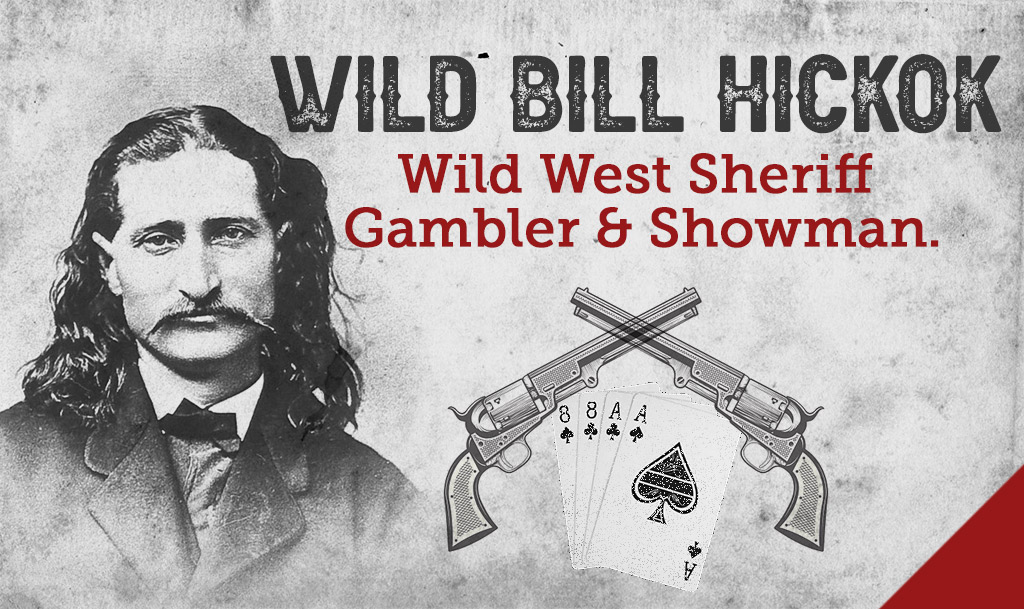

Born James Butler Hickok, everyone remembers him as “Wild Bill.” Many consider him the first famous gunfighter of the American West. During his relatively short life, he worked as a gold prospector, bodyguard, killer, lawman, army scout, gambler, and showman. He also met or worked with some of the Old West’s most famous (and infamous) figures, including “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Calamity Jane, John Wesley Hardin, and General George A. Custer.

Who was this man whose name became synonymous with handguns and violence as he became a legend during his lifetime? Like so many colorful historical figures, Hickok’s reported exploits are often challenging to confirm or disprove.

Still, most agree that Wild Bill was an anti-hero full of contradictions. On the one hand, he was a ruthless gunman who killed without conscience, but he could be a courteous gentleman dressing in the latest styles and charming the ladies. Let’s see if we can uncover the honest Wild Bill.

Young Hickok: Life Of Violence

Born on a farm in Illinois in 1837, James Hickok appeared fated to be a gunfighter from the start. As a young boy, he honed his shooting skills with lots of practice with a pistol, and by the age of 17, he left home looking for work to make the most of those skills.

He found his first opportunity in 1856 after landing in Kansas. The conflict over whether slavery should exist there was heating up, and Hickok joined the Free State Army of Jayhawkers, an antislavery vigilante group. While a Jayhawker, Hickok met 12-year-old William Cody, who would eventually become Buffalo Bill. Around the same time, Wild Bill became the bodyguard of General James Henry Lane, an abolitionist senator from Kansas.

What Guns Did Wild Bill Hickok Use?

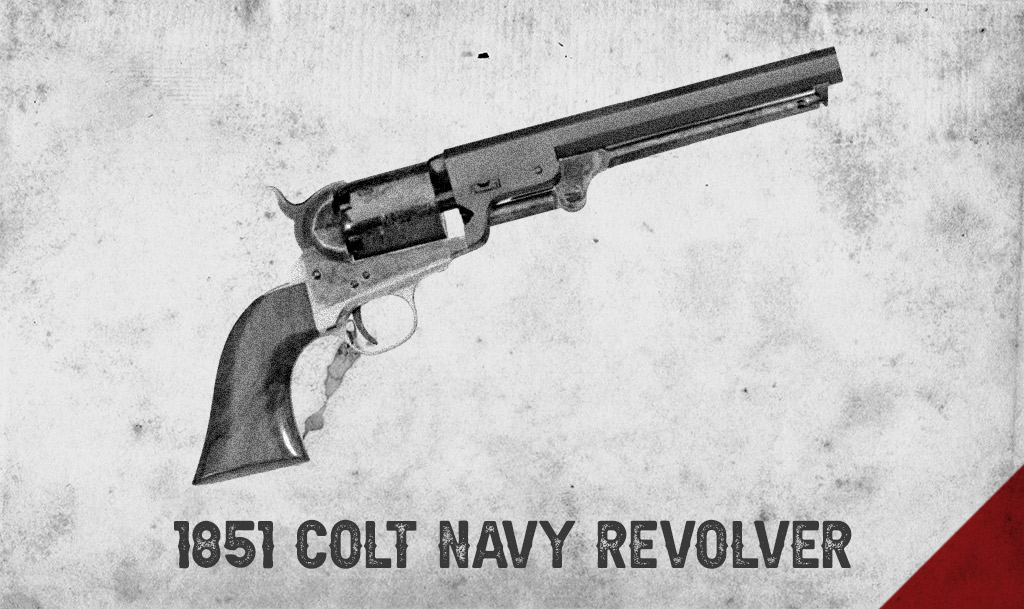

Wild Bill Hickok was known to carry a pair of .36-caliber Colt Navy pistols.

Hickok likely hunted game in Illinois with a flint or percussion lock shotgun, and when he arrived in Kansas, he reportedly carried a .44-caliber Colt Dragoon revolver. However, historians are unsure about all the weapons Wild Bill used.

There’s a general agreement that his favorite revolvers were a pair of .36-caliber Colt Navies, worn butt-forward in open holsters. Several years after the Civil War ended, he carried a couple of .38-caliber Colt Navy revolvers converted from percussion to accept either rim- or center-fire metallic cartridges. Wild Bill went to his rest with a .50-caliber Springfield Model 1870 rifle at his side.

The Making of a Legend: The McCanles Massacre

Many versions of the killing of David McCanles circulated for years after it occurred on July 12, 1861. One of those accounts was supplied by Hickok in 1867 and published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. In that account, Wild Bill outdraws and kills McCanles and five of his gang before besting three others in hand-to-hand combat. However, historians put forth a more plausible version.

McCanles was a disreputable bully demanding money from the manager of the Rock Street Station in the Nebraska Territory. Hickok, who worked for the parent company of the Pony Express, was in town recovering from a run-in with a bear and happened to be in the office when McCanles came in and threatened the manager, who owed him the money. At some point, a confrontation ensued. Things escalated after McCanles called Hickok “Duck Bill” – referring to his pointy nose and protruding lips.

Hickok supposedly pulled a pistol and killed McCanles on the spot. Although Hickok went to trial, a jury determined he acted in self-defense and acquitted him. After that, young James Hickok ceased to exist, and “Wild Bill Hickok” was born.

Wild Bill Hickok At War

From left, to right: Wild Bill Hickok, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Texas Jack Omohundro.

During the Civil War, Hickok became a teamster for the Union Army. He would later work as a civilian scout and provost marshal. After the war, Hickok continued barely skirting the wrong side of the law, and on July 21, 1865, he got involved in a Missouri shootout with a gunfighter named David Tutt.

Tutt flaunted a watch he won from Hickok in a poker game, leading to a faceoff in the Springfield town square. The duel, considered the first of its kind, ended when Wild Bill drew faster and shot more accurately, hitting Tutt in the heart. Hickok was once again arrested for murder, tried, and acquitted.

In 1866, Wild Bill guided Gen. William T. Sherman’s tour of the West. In 1867, he rode as a scout for Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock and Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry.

Hickok became the sheriff of Hays City, Kansas, in 1869. There, he reportedly killed several men during shootouts before taking over as the Abilene, Kansas marshal in 1871. Hickok met the notorious gunfighter, John Wesley Hardin, in this rough-and-tumble cattle town. By all accounts, the two gunslingers got along well, with Hardin remarking he thought highly of Wild Bill.

During another gunfight with a saloon owner named Phil Coe, Bill shot and killed the saloonkeeper. Then he reacted to someone running toward him by firing another shot. Unfortunately, that person was his deputy, Mike Williams. Hickok would lose his job over killing Williams, plus the other misconduct he’d been accused of in his career. Wild Bill would never fight another Wild West gun battle.

A Brief Time In The Spotlight

Hickok tried his hand at acting in Wild West shows, even producing his own show, The Daring Buffalo Chase of the Plains. That show didn’t work out, so in 1873, he joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s play, The Scouts of the Prairie, in Rochester, New York. Despite earning some much-needed money, Hickok disliked acting and was unhappy. He began drinking heavily and returned West in 1874.

Marriage & Death

Hickok married Agnes Lake in March 1876, but the marriage only lasted five months. He soon left his wife behind and headed for the gold mining town of Deadwood, South Dakota. By all accounts, he did more gambling than mining when he got there.

On the afternoon of August 1, 1876, Wild Bill Hickok was playing cards at Nuttal & Mann’s Saloon. Uncharacteristically, he had his back to the saloon door. This allowed a gunslinger named Jack McCall to walk up behind him and shoot him in the back of the head, killing him instantly. McCall claimed he was avenging his brother’s death at the hands of Hickok, but no one ever verified that. McCall was later tried, convicted, and hanged.

Wild Bill reportedly held two black aces and two black eights, plus an unknown “hole card” at his death. That hand has been known as a “Dead Man’s Hand” ever since.

Wild Bill Hickok’s Legacy

Hickok’s Dead Man’s Hand: A pair of black aces and a pair of black eights.

Hickok became a folk legend through television, movies, books, and music. Although many of his exploits were likely exaggerated, he’s noteworthy for his calm deportment under pressure and willingness to put himself in harm’s way. Despite his often-questionable methods, Wild Bill usually did what he thought was right.

No one ever bested Hickok in a fair fight, and it took a coward to do him in. It would be stretching things to call him a hero of the Old West, but he definitely was one of its larger-than-life characters!